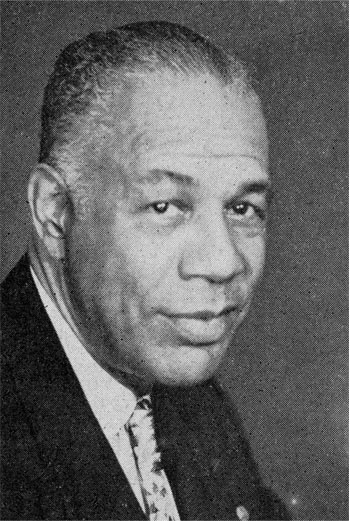

In this installment of our Hidden Voices series, we’re honoring Victor H. Green, a Harlem native who created the “Green Book” – a travel guide that helped thousands of African Americans safely navigate across the United States throughout the twentieth century.

Hidden Voices began as a collaboration between the NYC Department of Education and the Museum of the City of New York that was initiated to help City students learn about the countless individuals who are often “hidden” from traditional historical records. Each of the people highlighted in this series has made a positive impact on their communities while serving as outstanding examples of leadership, advocacy, and community service.

Today, we are featuring Victor Hugo Green, a postal worker from Harlem who created the “Negro Motorist/Travelers’ Green Book”, an annual travel and vacation guide published 1936–67 that helped readers identify and travel to businesses that accepted Black customers back during an era where legalized segregation between the races was the norm.

Freedom. Mobility. Independence.

These were the promises of one of the 20th century’s most important consumer products: the automobile.

Not long after Ford’s introduction of its groundbreaking Model T in 1908, the automobile transformed life in the United States. By the early 1930s, cars became about as “American” as apple pie and baseball, as millions of Americans across the country bought cars and took to the road for work, school, and leisure.

Automobiles, which fueled the Great Migration, provided Black families with a level of mobility and personal freedom that they did not have previously. By the 1950s, almost 500,000 Black families owned at least one car. (Photo by H. Armstrong Roberts. Original can be found online via Getty Images.)

Automobiles, which fueled the Great Migration, provided Black families with a level of mobility and personal freedom that they did not have previously. By the 1950s, almost 500,000 Black families owned at least one car. (Photo by H. Armstrong Roberts. Original can be found online via Getty Images.)Unfortunately, however, the “freedom” that cars had come to represent at that time was not accessible to all Americans. Just as the country’s economy and transportation infrastructure completely changed following the mass adoption of automobiles, the United States was experiencing the peak of its Jim Crow era—a period of time in American history when laws were enacted in municipalities across the country that required physical segregation between Black and white Americans in public and private spaces.

During this era, many businesses across the country, particularly in the Deep South, were legally required to determine which customers to serve based on the color of their skin. Thanks to segregation, whatever freedom and independence that had been promised to automobile owners during the first half of the 20th century came with conditions and exceptions for many Black Americans across the United States. Roadside businesses that many American drivers took for granted during their road journeys, including hotels, gas stations, restaurants, and bathrooms, would often deny Black travelers access and force them to continue driving for miles before reaching friendlier businesses or locations.

To prepare for travel through these segregated areas, Black families often packed their cars with extra food, water, fuel, blankets, and other amenities so that they did not have enter unfriendly businesses and potentially endanger themselves. Driving through an unknown city, state, or region without prior preparation could be extremely dangerous and even life-threatening—mistakenly stopping in the wrong town or the wrong business could mean the difference between life and death. This was especially true in places called “sundown towns,” where predominantly white communities used threats of violence or death to force Black travelers into leaving. These towns got their names because many of them posted signs that warned Black visitors to leave by sundown, “or else.”

Victor Green knew from firsthand experience what traveling across the U.S. was like as Black man—during the 1920s, he managed his brother-in-law, Robert Duke, who toured across the country as a musician.

Victor Green knew from firsthand experience what traveling across the U.S. was like as Black man—during the 1920s, he managed his brother-in-law, Robert Duke, who toured across the country as a musician.It was during this period of time that Victor Hugo Green (1892–1960), a postal worker living in Harlem, made the observation that, “For the Negro traveler, whether on business or pleasure, there was always trouble finding suitable accommodation in hotels and guest houses where he would be welcome.”

By 1936, Green said it was time he “thought of doing something about this,” and imagined creating a “listing, as a comprehensive as possible, of all the first-class hotels throughout the United States that catered to negroes.” Inspired by the Jewish Vacation Guide, a guidebook published and used by Jewish Americans at the time to navigate safely around the country in the face of widespread antisemitism, he compiled data on hotels, restaurants, and gas stations located in the New York area that accepted Black travelers, and created the first edition of The Negro Motorist Green Book, which he published later that year.

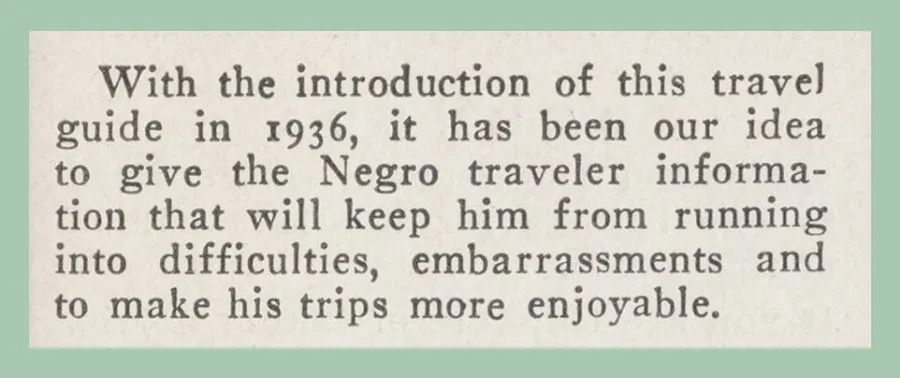

The purpose of the “Green Book” as it became known colloquially over time, was summed up well in a later edition of the travel guide: in 1949, the book’s introduction pointed out the disparate challenges Black travelers experienced: “If you’re traveling, you don’t have to worry about accommodations—whether this place will take you in or that place will sell you food. That is if you’re white and gentile. If you’re not, you have to travel a careful route like seeking oases in a desert.”

Green’s travel guide came about at the peak of the Great Migration, when more than six million African Americans who moved from the rural south to live and work in northern and western cities. In fact, Green’s wife, Alma Duke, was one of the millions of Americans who made this journey, leaving Virginia for New York. It was after marrying her in 1918 when they first moved to Harlem—where nearly 175,000 African Americans also lived at the time. New arrivals like Alma helped turn Harlem into the largest Black neighborhood in the nation and helped spark the cultural movement known today as the Harlem Renaissance.

This excerpt from the beginning of the 1936 edition of the "Negro Motorist Green Book" hints at the "difficulties" that Jim Crow created for Black drivers of the time.

This excerpt from the beginning of the 1936 edition of the "Negro Motorist Green Book" hints at the "difficulties" that Jim Crow created for Black drivers of the time.It is no question that Black culture was thriving in Harlem at the time Green arrived, but the publication of the Green Book, and the massive popularity it would quickly garner, makes clear that northern cities like New York were not altogether welcoming places for Black Americans. It shows that the problems of segregation and Jim Crow laws were not exclusive to the south and that racial discrimination was also deeply prevalent in the northern United States, too.

In fact, the success of Green’s initial travel guide led him to expand his efforts in later editions to account for travelers beyond New York to include cities and towns across most of the United States and even in countries like Mexico and Canada. He would also begin to list different types of businesses, including barbers shops, beauty parlors, tailors, and local attractions, aiming to provide readers with access to all the information they could need about wherever they were going, and whatever they needed when they got there.

From 1936 until its last edition in 1967, the Green Book travel guide was published annually except during World War II. Publication would continue even after Victor Green’s passing in 1960, when his widow, Alma, took over the guide. Before he died, he wrote in the 1948 edition of the book that, “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal rights and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication, for then we can go wherever we please…. But until that time comes, we shall continue to publish this information for your convenience each year.”

The final edition was published in 1967, after the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 made discrimination on the basis of race illegal. With Jim Crow and “separate but equal” no longer the law of the land, the publication of the Green Book became, as Green hoped it one day would, unnecessary.

Today, the Schomburg Center at the New York Public Library holds the largest collection of Green Books, available online through their digital collections.

Sources

- Blakemore, E. “How Automobiles Helped Power the Civil Rights Movement.” Smithsonian Magazine. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-automobiles-helped-power-civil-rights-movement-180974300

- Blanke, D. “Rise of the Automobile.” TeachingHistory.org. Available online: https://teachinghistory.org/history-content/beyond-the-textbook/24073

- Brown, D. L. “Life or Death for Black Travelers: How Fear Led to “The Negro Motorist Green-Book.” The Washington Post, 28 October, 2021. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2017/06/01/life-or-death-for-black-travelers-how-fear-led-to-the-negro-motorist-green-book

- Green, V.H. The Negro Motorist Green Book Collection (1936–1967). Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books Division, New York Public Library. Available online: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/the-green-book#/?tab=about

- “Harlem Renaissance.” History.com, 29 October, 2009. Available online: https://www.history.com/topics/roaring-twenties/harlem-renaissance

- “Harlem’s Victor Hugo Green’s The Green Book.” Harlem World Magazine, 11 August, 2020. Available online: https://www.harlemworldmagazine.com/harlems-victor-hugo-greens-the-green-book/

- Henry, C. A Brief History of Civil Rights in the United States: Jim Crow Era. Howard University School of Law, 6 January, 2023. Available online: https://library.law.howard.edu/civilrightshistory/blackrights/jimcrow

- “The Great Migration.” History.com, 30 August, 2022. Available online: https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/great-migration

- Lockhart, P.R. “A New Documentary Shows How the Real Green Book Helped Black Motorists.” Vox, 25 February, 2019. Available online: https://www.vox.com/culture/2019/2/22/18235335/green-book-guide-to-freedom-documentary-oscars

- McHugh, J. “The Jewish Travel Guide That Inspired the ‘Green Book.'” The Washington Post, 3 April, 2022. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2022/04/03/jewish-vacation-guide-green-book/

- “A New African American Identity: The Harlem Renaissance.” National Museum of African American History and Culture at the Smithsonian. Available online: https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/new-african-american-identity-harlem-renaissance

- Petras, G., and Loehrke, J. “Green Book, in Detail: Learn about Guide that Helped Black Travelers.” USA Today Travel, 19 February, 2021. Available online: https://www.usatoday.com/in-depth/travel/2021/02/19/black-history-month-inside-green-book-travel-guide/4357851001/

- Pickett, N.M. “Victor H. Green—Author and Pioneer: Commemorating 2021 National African American History Month.” Highway History—U.S. Department of Transportation, 2021. Available online: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/highwayhistory/green.cfm

- “Plessy v. Ferguson.” Oyez. Available online: https://www.oyez.org/cases/1850-1900/163us537

- Taylor, C. “Mapping the Green Book.” YouTube, 11 February, 2021. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QIZLDmF_vko

- Wallenfeldt, J. “The Green Book.” Encyclopedia Brittanica, 19 October, 2022. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/The-Green-Book-travel-guide

- “The U.S. Home Front During World War II.” HISTORY.com, 7 June, 2019. Available online: https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/us-home-front-during-world-war-ii

Images found in banner image, beginning from left to right; Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; the Victor H. Green & Co.; and Ben Shahn on behalf of the Farm Security Administration.