Hidden Voices, our ongoing series celebrating the lives of individuals who are often "hidden" from traditional historical records, continues with our profile of Bernice Sandler, the first chair of the National Advisory Council on Women's Educational Programs, and champion of the groundbreaking Title IX law that transformed student athletics in the United States.

Hidden Voices began as a collaboration between the NYC Department of Education and the Museum of the City of New York that was initiated to help City students learn about the countless individuals who are often “hidden” from traditional historical records. Each of the people highlighted in this series has made a positive impact on their communities while serving as outstanding examples of leadership, advocacy, and community service.

Today, we’re telling the story of Bernice Sandler, first Chair of the National Advisory Council on Women’s Educational Programs and champion of the groundbreaking Title IX law that transformed student athletics and gender equity in the United States.

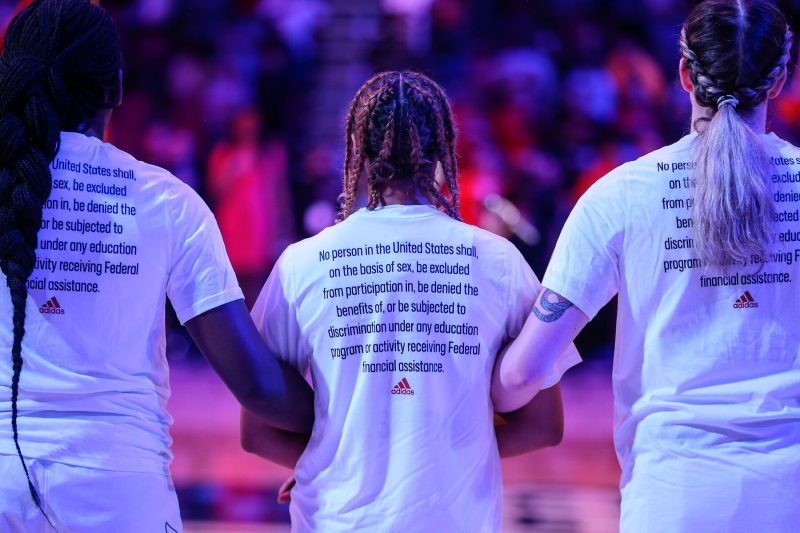

Half a century ago, 37 words changed American education and student athletics forever.

Over 50 years ago, President Richard Nixon signed into law the Education Amendments of 1972, a sweeping piece of legislation that affected federal education regulations and funding. Buried in the bill where hardly anyone would notice was one sentence—only 37 words long—that would change the face of education for women and girls across the United States from that moment on:

“No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Dr. Bernice Sandler, tireless advocate. (Photo credit: McClatchy-Tribune/Alamy)

Dr. Bernice Sandler, tireless advocate. (Photo credit: McClatchy-Tribune/Alamy)Today, we know these words as Title IX, the transformational law that banned sex discrimination in education—a law that could not have been passed without the work of Dr. Bernice Sandler.

Dr. Sandler, born in Brooklyn in 1928, was perhaps an unlikely person to become the “Godmother of Title IX,” as she is often referred to today. She didn’t always consider herself a feminist, and she once wrote that she was “somewhat ambivalent about the women’s movement” that was gaining steam in the 1960s. But even before she became involved in activism, or before the terms for “sexism” and “sex discrimination” even existed, Sandler still recognized that she had received fewer opportunities in her own life because she was a woman; as a child, for example, she was not allowed to use the slide projector in her Brooklyn classroom, nor was she allowed to become a crossing guard – activities which were reserved for the boys in her class.

Sandler wasn’t alone: before Title IX was passed, schools and universities severely limited opportunities for girls and women. In many high schools, for example, girls could not take “shop” or aeromechanics classes (nor could the boys enroll in home economics), and in some colleges, where few women were being admitted in the first place, female students were often not allowed to major in certain subjects, like chemistry. In women’s athletics, one of the areas that Title IX is most associated with today, women’s teams often had lower budgets, unpaid coaches, and only had access to old or used equipment (if they had any at all) that was handed down when the men’s teams got something new. There were no scholarship opportunities for female athletes, either. The poor quality and lack of opportunity in women’s sports programs had a clear effect on participation: in 1971, the year before the law passed, fewer than 300,000 girls participated in high school sports across the entirety of the United States — just 8% of the number of boys participating at the same level at that time.

Students were not the only ones dealing with limitations because of their gender either, as many undergraduate schools refused to hire female faculty, and those who did get jobs often received lower salaries than their male colleagues. In fact, as Sandler entered adulthood, she encountered this problem firsthand. After graduating from Erasmus Hall High School, she received a bachelor’s degree in psychology from Brooklyn College in 1948 and a Master’s degree from the City College of New York, but her job opportunities were still limited both because of her gender, and because she was Jewish. Despite the discrimination she had faced, she decided to pursue a doctorate at the University of Maryland even after she was told that she was “too old” and “just a housewife who went back to school.” Nevertheless, Sandler completed her degree in 1969, and following her graduation, began teaching part time at the University. However, in spite of her qualifications, she was repeatedly rejected for full-time teaching positions in her department because, she was told, “you come on too strong for a woman.” Sandler credited this as the moment when she started on the path towards lifelong advocacy for women in academia and education–given what happened next, perhaps it is these seven words, rather than the 37 contained in Title IX itself, that changed student athletics forever in the United States.

Dr. Sandler credits the moment she was told that she was "too strong for a woman," for giving her the inspiration she needed to start advocating for women's rights in academia and education. (Photo credit: National Organization for Women)

Dr. Sandler credits the moment she was told that she was "too strong for a woman," for giving her the inspiration she needed to start advocating for women's rights in academia and education. (Photo credit: National Organization for Women)Around this time, Sandler became involved with the Women’s Equity Action League (WEAL) as the Chair of the Action Committee for Federals Contract Compliance. In this role, she discovered Executive Order 11375, a little-known law that stated that federal companies could not discriminate based on race, color, religion, and national origin – later amended to also include gender discrimination. Because many colleges had federal contracts, Sandler realized that this law applied to them, too, which meant it was illegal for them not to hire women. Armed with this knowledge, Sandler filed sex discrimination charges against 250 schools between 1969 and 1971. In 1970, with the help of WEAL, she would also use this law to file a class-action lawsuit against all universities in the United States that received federal contracts.

That summer, Sandler also testified at the first congressional hearing dealing with sex discrimination in education and employment. Notably, when asked to testify at the hearings, the representative for the American Council on Education, one of the most important groups focused on higher education at the time, declined, stating that “There is no sex discrimination in higher education,” and that “even if there was, it wasn’t a problem.” After the hearings, Sandler also became Educational Specialist for the House of Representatives Special Subcommittee on Education, making her the first person ever appointed to a Congressional committee staff to work specifically on women’s issues. In that role, Sandler authored the first ever federal report on gender discrimination in education in 1971.

By the following year, efforts to pass Title IX had begun, and advocates inside and outside of the government used much of Dr. Sandler’s work documenting and investigating cases of sex discrimination as the basis for needing such a law. However, even with all of the hard work and research that laid the groundwork for Title IX, it was not a sure thing that the bill would pass.

For that to happen, Sandler and other activists counted on their politically savvy allies in Congress, like Congresswomen Edith Green and Patsy Takemoto Mink, along with Senator Birch Bayh, who were considered some of Title IX’s biggest champions of Title IX — who recognized that in order to avoid the controversies and pitfalls that had prevented the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, they needed to keep the law “under the radar and broad.” Representative Green even discouraged Sandler and other advocates from lobbying for the bill because “if [they] started to lobby, people would ask questions and realize about what Title IX would do.” Instead, they decided they needed to move the law forward “very subtly and quietly.”

Their strategy worked, and as a result, when President Nixon signed the bill on June 23 there was little fanfare surrounding the gender discrimination provisions. In fact, the President didn’t actually mention Title IX at all in his signing statement, focusing instead on his hopes to weaken federal involvement in busing programs to racially desegregate public schools. The bill’s passage did make front-page news in the New York Times, but Title IX itself was relegated to a single bullet point. In 2007, Sandler wrote that when the law passed, “a new era had begun, but few realized that this was a landmark bill which would affect millions of girls and women and change our schools and colleges forever.”

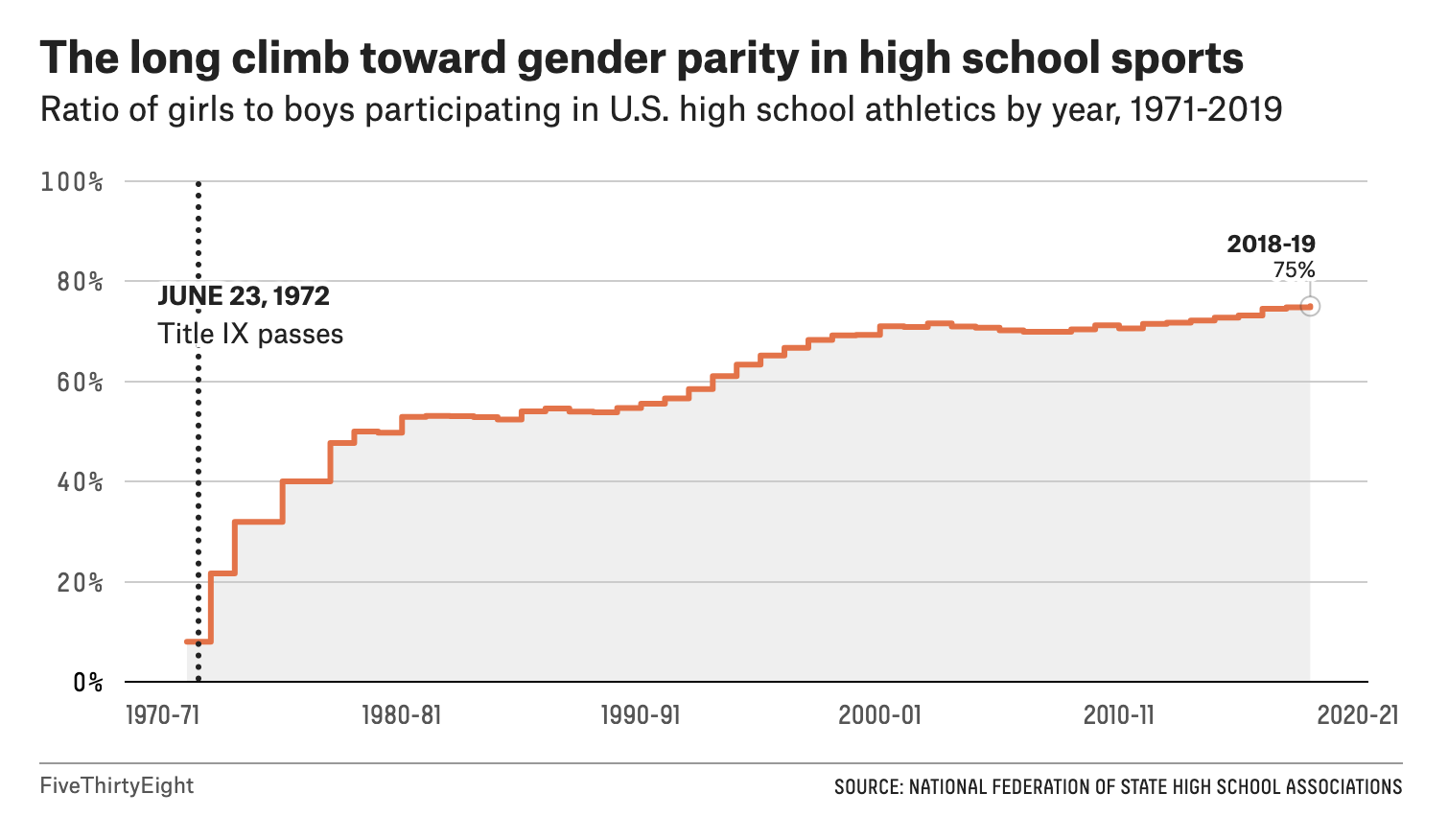

When Title IX was first passed, women made up 15% of all college athletes. Today, women make up 44 percent of all college athletes. ("Gender Parity in High School Sports" graphic by FiveThirtyEight)

When Title IX was first passed, women made up 15% of all college athletes. Today, women make up 44 percent of all college athletes. ("Gender Parity in High School Sports" graphic by FiveThirtyEight)Perhaps nowhere was this sentiment more true than in athletics: despite being regularly associated with women’s sports today, the original text of Title IX does not include any mention of sports at all, and so many stakeholders, including some of the law’s biggest supporters, did not anticipate the major change that was coming for female athletes. Once Title IX had passed, even Dr. Sandler said that “[her] understanding of Title IX’s impact on sports was something like this: ‘Isn’t this nice! Because of Title IX, at the annual Field Day events in schools, there will be more activities for girls.’” But there was almost immediately a noticeable effect: only one year after Title IX went into effect, female participation in high school sports had risen by 178%, and by the end of the first decade that Title IX was law, participation had reached over 53% that of their male peers.

Though there is still, even today, a ways to go to achieve true gender equality between men’s and women’s athletics, this major increase in participation explains why so many people think of Title IX as a “sports law” even if the bill’s authors did not. But 50 years later, it is clear that Title IX is not only a law that has benefited student athletes, either. In fact, Dr. Sandler herself said that the law was the most important piece of legislation since women got the right to vote, and compared the transformational effects it had to the Industrial Revolution. There are a lot of reasons why she might have thought so: thanks to Title IX, opportunities for women in the classroom and the workplace have dramatically expanded, and young girls can now aspire to be lawyers, doctors, fire fighters, and grow up to work in professions that were previously considered “unsuitable” for women. The number of female students enrolled in undergraduate and graduate programs has continued to rise, and thousands of women faculty members receiving pay raises to ensure their salaries are equitable with their male counterparts. Title IX also increased academic research into gender discrimination, allowing it to be seen as more “legitimate,” and giving us more insight into the areas where progress is still needed. In 1992, yet another transformational change came with the Supreme Court decision in Franklin v. Gwinnett County Schools, in which the justices ruled that sexual harassment in public schools should be considered a violation of Title IX, a victory that provided legal protection for students that had experienced such harassment.

Title IX may have passed with little fanfare back in 1972, but there's no denying the monumental effect it has had on youth sports. Today, three million more girls have the opportunity to participate in athletics than they did over five decades ago, before Title IX became law. (Photo by Travis Heying/FRE AP, via Associated Press)

Title IX may have passed with little fanfare back in 1972, but there's no denying the monumental effect it has had on youth sports. Today, three million more girls have the opportunity to participate in athletics than they did over five decades ago, before Title IX became law. (Photo by Travis Heying/FRE AP, via Associated Press)Sandler continued to be involved in advocacy related to women’s education long after Title IX was passed, until her death in 2019 at age 90. She was appointed by Presidents Ford and Carter to be the first Chair of the National Advisory County on Women’s Educational Programs, assuming the role in 1975. She later served as a Senior Scholar in Residence at the Women’s Research and Education Institute in Washington, DC, giving more than 2,500 presentations on strategies and policies to prevent and respond to sex discrimination and helping to advance awareness and research into education equity for women. Sandler received 12 honorary degrees throughout her life, and in 2013, was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

Without her continued hard work and dedication, the progress that has been made towards equity so far would not have been possible. But even Dr. Sandler acknowledged that he country still has a long way to go: “We have only taken the very first steps,” she said, “of what will be a very long journey.”

Sources

- Alexander, K. L. (2019). “Bernice Sandler (1928-2019),” National Women’s History Museum. Available online: womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/bernice-sandler

- American Civil Liberties Union. (2012). “Title IX – The Nine,” American Civil Liberties Union. Available online: aclu.org/other/title-ix-nine

- Blakemore, E. (2022, June 22). “Title IX at 50: How the U.S. law transformed education for women,” National Geographic. Available online: nationalgeographic.com/history/article/the-history-and-legacy-of-title-ix

- Chrisler, J. C., & McHugh, M. C. (2020). “Bernice Resnick Sandler (1928-2019),” The American Psychologist, 75(1), 119–120. Available online: doi.org/10.1037/amp0000527

- Daley, J. (2019, January 11). “Remembering “Godmother of Title IX” Bernice Sandler,” Smithsonian Magazine. Available online: smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/godmother-title-ix-bernice-sandler-180971246/

- “Education Amendments of 1972.” (2022) Wikipedia.org. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Education_Amendments_of_1972

- “Franklin v. Gwinnett County Public Schools.” (1991). Oyez. Available online: oyez.org/cases/1991/90-918

- Goldman, T., & Chappell, B. (2019, January 10). “How Bernice Sandler, ‘Godmother of Title IX,’ Achieved Landmark Discrimination Ban,” NPR. Available online: npr.org/2019/01/10/683571958/how-bernice-sandler-godmother-of-title-ix-achieved-landmark-discrimination-ban

- Grigoriadis, V. (2019, December 29). “Bernice Sandler: The Godmother of Title IX,” Politico. Available online: politico.com/news/magazine/2019/12/29/bernice-sandler-the-godmother-of-title-ix-088277

- Hardage Lee, H. (2022, June 23). “The ripple effect of the landmark Title IX continues on its 50th anniversary,” The Hill. Available online: thehill.com/opinion/congress-blog/3534426-the-ripple-effect-of-the-landmark-title-ix-continues-on-its-50th-anniversary/

- Marcus, B. (2019, January 10). “You May Not Know It, But Dr. Bernice Sandler Made Your Life Better,” Forbes. Available online: forbes.com/sites/bonniemarcus/2019/01/10/you-may-not-know-it-but-dr-bernice-sandler-made-your-life-better/

- National Women’s Hall of Fame. (2013). “Sandler, Bernice Resnick,” National Women’s Hall of Fame. Available online: womenofthehall.org/inductee/bernice-resnick-sandler/

- Negley, C. (2019, January 8). “Dr. Bernice Sandler, ‘godmother of Title IX,’ dies at 90,” Yahoo Sports. Available online: sports.yahoo.com/dr-bernice-sandler-godmother-title-ix-dies-90-213545800.html

- Nixon, R. (1972). “Statement on Signing the Education Amendments of 1972,” The American Presidency Project. Available online: presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/statement-signing-the-education-amendments-1972

- NOW Press. (2019, January 8). “Celebrating The Life and Work of Bernice Sandler,” National Organization for Women. Available online: now.org/media-center/press-release/celebrating-the-life-and-work-of-bernice-sandler/

- Paine, N. (2022, June 1). “What 50 Years of Title IX Has—And Hasn’t—Accomplished,” FiveThirtyEight. Available online: fivethirtyeight.com/features/paine-title-ix/

- Peterson, A. M. (2019, March 22). “The Godmother of Title IX,” Brooklyn College. Available online: brooklyn.cuny.edu/web/news/bcnews/bcnews_190322.php

- Sandler, B. R. (2007). “Title IX: How We Got It and What a Difference It Made,” Cleveland State Law Review, pgs. 55(4), 473–489.

- Seelye, K. Q. (2019, January 8). “Bernice Sandler, ‘Godmother of Title IX,’ Dies at 90,” The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/08/obituaries/bernice-sandler-dead.html

- Semple, R. B. (1972, June 24). “President Signs School Aid Bill; Scores Congress,” The New York Times, pgs 1, 15. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/1972/06/24/archives/president-signs-school-aid-bill-scores-congress-terms-rejection-of.html

- The United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division. (2021, August 12). “Title IX Legal Manual,” The United States Department of Justice. Available online: justice.gov/crt/title-ix

- “Title IX and Sex Discrimination,” (2021, August 20). US Department of Education. Available online: www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/tix_dis.html

- Tugend, A. (2022, April 27). “Title IX at 50: How it Changed Congress, Campuses and Sports,” The New York Times. Available online: nytimes.com/2022/04/27/arts/design/new-york-historical-society-title-ix-50.html

- Tumin, R. (2022, June 23). “Fifty Years On, Title IX’s Legacy Includes Its Durability,” The New York Times, pg. 30. Available online: nytimes.com/2022/06/23/sports/title-ix-anniversary.html

- Winslow, B. “The Impact of Title IX,” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Available online: gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/essays/impact-title-ix

- Wulf, S. (2012, March 22). “Title IX: 37 Words That Changed Everything,” ESPN. Available online: espn.com/espnw/title-ix/story/_/id/7722632/37-words-changed-everything

Banner photo by Aaron Ontiveroz/The Denver Post via Getty Images.