Paving the Way for Brown v. Board: The Mendez Family’s Fight Against School Segregation

Hidden Voices began as a collaboration with the Museum of the City of New York to help City students learn about the countless individuals who are often “hidden” from traditional historical records. Each of the people highlighted in this series has made a positive impact on their communities while serving as outstanding examples of leadership, advocacy, and community service.

Today, we're sharing the story of Sylvia Mendez and her family, who led a groundbreaking legal fight to end school segregation in California. Their case, Mendez v. Westminster, helped pave the way for Brown v. Board of Education and showed how courage, community, and determination can spark lasting change in the fight for educational equality.

When thinking about the history of school segregation in the United States, the 1954 Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education might come to mind. That landmark decision declared that separating children into different schools based on race was unconstitutional, overturning the legal principle of “separate but equal” that had previously permitted race discrimination in schools across the country.

Brown did not exist in a vacuum, however; the lawyers who argued against segregation in 1954 built on earlier desegregation cases to strengthen their arguments. Many of them are referenced in the arguments made during Brown v. Board, but one critical case goes unmentioned in the legal record, despite the key role it played—a case brought seven years earlier, best known as Mendez v. Westminster.

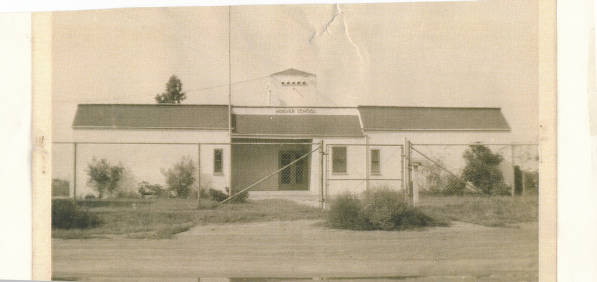

In 1944, Sylvia Mendez and her brothers were denied enrollment at Westminster’s Seventeenth Street School in Orange County, California. Their cousins, who had lighter skin and a French-sounding last name, were accepted. But Sylvia and her brothers, who had darker skin and a Mexican surname, were told they had to attend Hoover Elementary—the “Mexican school.”

Hoover Elementary was underfunded and poorly maintained. It lacked basic playground equipment and had lunch tables placed near cow pastures. The message was clear: children of Mexican descent were not seen as deserving of the same educational opportunities as their white peers.

Gonzalo and Felícitas Mendez, Sylvia’s parents, were determined to fight this injustice. Gonzalo, a Mexican immigrant who had worked his way up from farm laborer to farm manager, had always dreamed of owning his own land. During World War II, he leased a farm from the Munemitsu family, Japanese Americans who had been sent to an internment camp. That lease gave the Mendez family the financial stability to take legal action. Felícitas took over management of the farm so Gonzalo could dive head-first into the lawsuit, determined to get justice for his family and his community.

With the help of civil rights attorney David Marcus, the Mendez family filed a lawsuit in federal court. They were joined by four other families—the Guzmáns, Palominos, Estradas, and Ramirezes—who had also experienced school segregation in their respective school districts. Together, they went to court on behalf of around 5,000 children of Mexican descent in Orange County.

The Legal Battle: Mendez v. Westminster

Filed in 1945, Mendez v. Westminster challenged the segregation policies of four school districts: Westminster, Garden Grove, El Modena, and Santa Ana. The families argued that separating children based on their Mexican heritage violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which guarantees equal protection under the law.

The school districts claimed the children were being separated due to language deficiencies. However, many parents and students testified that the children in fact spoke English fluently and had never been tested. It became clear that the separation was driven by ethnicity and appearance—not by any actual language barriers.

At the time, Mexican Americans were legally classified as white under US law. David Marcus, the attorney for the Mendez family, used this classification to argue that the segregation of Mexican American children was not based on race, but on national origin or ethnicity, which was not permitted under California law.

This approach allowed Marcus to sidestep the precedent set by Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which had affirmed the constitutionality of racial segregation under the doctrine of “separate but equal.” Since the law did not recognize Mexican Americans as a separate race, Marcus argued that separating them from other white students had no legal basis.

His arguments worked: In 1946, Judge Paul J. McCormick ruled in favor of the Mendezes and the other Mexican American families. He stated that segregating children based on ancestry was unconstitutional and harmful to their education and development. His decision included a powerful statement:

“A paramount requisite in the American system of public education is social equality. It must be open to all children by unified school association regardless of lineage.”

This ruling marked the first time a federal court declared that school segregation was unconstitutional, setting a powerful precedent not just in California, but around the nation. The case drew national attention and support from major civil rights organizations, particularly once the case was going through the appeals process.

By that time, the NAACP, American Jewish Congress, Japanese American Citizens League, and others had learned of the case and filed amicus curiae briefs—legal documents submitted by outside groups to offer additional perspectives—in support of the Mendezes. These briefs emphasized the psychological harm caused by segregation and argued that it violated the constitutional rights of all children.

The Legacy of Mendez

Just months after the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the Mendez decision, requiring schools to integrate Mexican American children, California Governor Earl Warren signed legislation that officially ended school segregation in the state. This made California the first state in the nation to outlaw public school segregation—an extraordinary shift in policy that directly followed the momentum of the Mendez case.

Warren’s involvement didn’t end there. Seven years later, after becoming Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, he authored the unanimous opinion in Brown v. Board of Education, declaring that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional nationwide.

The legal reasoning and social science arguments used in Mendez—including expert testimony on the psychological harm caused by segregation—influenced the strategy used by the NAACP in Brown. Thurgood Marshall, the NAACP lawyer who successfully argued Brown, also helped author the organization's brief for the Mendez appeal, marking one of the first times social science research was used in a desegregation case.

Though Mendez did not reach the Supreme Court, it helped lay the legal and moral foundation for the national civil rights movement. It demonstrated that segregation harmed children, violated constitutional protections, and could be successfully challenged in court—even by ordinary families. It also inspired future legal battles and civil rights activism across the country.

The case also demonstrated the power of collective action—within the Mexican American community and across diverse groups who united to challenge injustice. Their unity showed that civil rights struggles are interconnected and that progress often comes from collective effort.

After the case, the Mendez children were able to attend integrated schools moving forward, despite continued efforts to reverse integration in Orange County and beyond. Despite facing discrimination after transferring to the formerly white school at first, Sylvia Mendez persisted and continued her education. She later became a nurse. But as an adult, she realized that few people knew about her family’s role in ending school segregation. Before her mother died, Sylvia promised her that she would change that, and dedicated herself to sharing their story. To this day, she visits schools and communities across the country to tell them about the importance of Mendez v. Westminster.

In 2011, President Barack Obama awarded Sylvia the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in the United States. In 2022, the Mendez Tribute Monument Park opened in Westminster, honoring the family’s legacy. In addition, the U.S. Postal Service honored the Mendez family with a stamp in 2007, commemorating their fight for equality. The farm the Mendez family once leased from the Munemitsus is now the site of two public schools, and in 1998, the Santa Ana School Board named a new school in honor of Gonzalo and Felícitas Mendez.

Sylvia Mendez continues to remind audiences that the fight for justice is ongoing. Her family’s story is not just about one court case—it’s about the courage to stand up, the strength of community, and the belief that every child deserves an equal education.

As Felícitas Mendez once reflected, the case was not just for her and her family, but “for their children, and their children, and for [the entire] community.”

Sources

- Aguirre, F. P., Bowman, K. L., Mendez, G., Mendez, S., Robbie, S., & Strum, P. (2014). Mendez v. Westminster: A Living History. Michigan State Law Review, 2014(3), 401–427. https://doi.org/10.17613/n7xc-xc04

- Antonio, M. J., Hurtado, M., Ryerson, J., & Eveland, A. (2023). Entangled Inequalities: Japanese Incarceration and Mendez, et al. v. Westminster School District of Orange County, et al. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/entangled-inequalities-japanese-incarceration-and-mendez-et-al-v-westminster-school-district-of-orange-county-et-al.htm

- Arriola, C. (1995). Knocking on the School House Doors: Mendez v. Westminster, Equal Protection, Public Education, and Mexican Americans in the 1940s. Berkeley La Raza Law Journal, 8, 166–207. https://www.nycourts.gov/ip/judicialinstitute/The_Latino_Judges_Association/pdfs/6.%20Knocking%20on%20the%20Schoolhouse%20Door.pdf

- Behring Center. (2004). In Pursuit of Equality—Separate Is Not Equal. Separate Is Not Equal: Brown v. Board of Education. https://americanhistory.si.edu/brown/history/2-battleground/pursuit-equality-2.html

- Bermudez, N. (2017). Reinscribing History: “Mendez et al. V. Westminster et al.” from the Standpoint of Mexican Origin Women. American Studies, 56(2), 9–30. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44982470

- Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1). (1954). Oyez. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1940-1955/347us483

- Blakemore, E. (2018, March 27). How Dolls Helped Win Brown v. Board of Education. HISTORY. https://www.history.com/articles/brown-v-board-of-education-doll-experiment

- Contreras, R. (2025, January 7). Federal courthouse renamed after Latino family in segregation fight. Axios. https://www.axios.com/2025/01/07/federal-courthouse-renamed-mendez-latino-segregation

- Donato, R., & Hanson, J. S. (2012). Legally White, Socially “Mexican”: The Politics of De Jure and De Facto School Segregation in the American Southwest. Harvard Educational Review, 82(2), 202-225,325-326. Research Library. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1022987077?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true&sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals

- FedBar Blog. (2021, June 16). Mendez v. Westminster: The Mexican-American Fight for School Integration and Social Equality Pre-Brown v. Board of Education. Federal Bar Association. https://www.fedbar.org/blog/mendez-v-westminster-the-mexican-american-fight-for-school-integration-and-social-equality-pre-brown-v-board-of-education/

- Foley, N. (2005). Over the Rainbow: Hernandez v. Texas, Brown v. Board of Education, and Black v. Brown. Chicana/o Latina/o Law Review, 25(1), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.5070/C7251021158

- Gonzalez, G. G. (1996). Chicano Educational History: A Legacy of Inequality. Humboldt Journal of Social Relations, 22(1), 43–56. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23263041

- Hurtado, M., & Antonio, M. J. (2023). Setting the Precedent: Mendez, et al. v. Westminster School District of Orange County, et al. and the US Courthouse and Post Office. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/setting-the-precedent-mendez-et-al-v-westminster-school-district-of-orange-county-et-al-and-the-us-courthouse-and-post-office.htm

- Macías, F. (2014, May 16). Before Brown v. Board of Education There Was Méndez v. Westminster [In Custodia Legis]. The Library of Congress. https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2014/05/before-brown-v-board-of-education-there-was-mendez-v-westminster

- Mendez et al. v. Westminster School Dist. of Orange County et Al., 64 Federal Supplement 544 (U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California 1946). https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/64/544/1952972/

- Mendez, F. Felícitas and Gonzalo Mendez [Photograph]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Felicita_and_Gonzalo.jpg

- Mendez, S. (1944). Sylvia Mendez, Age 8 [Photograph]. Duke University. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sylvia_Mendez.jpg

- Mendoza, N. (2025). The Mendez Family: The Mexican American and Puerto Rican Family Who Legally Challenged School Segregation in California. In Hidden Voices: Latines in United States History (pp. 261–278). New York City Public Schools. https://www.weteachnyc.org/resources/resource/hidden-voices-latines-in-united-states-history/

- Obama Presidential Library. (2011, February 16). Presidential Medal of Freedom Recipient: Sylvia Mendez. Collection BHO-WHCA: Records of the White House Communications Agency (Obama Administration). https://docsteach.org/document/presidential-medal-of-freedom-sylvia-mendez/

- Plessy v. Ferguson. (1896). Oyez. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1850-1900/163us537

- Powers, J. M. (2014). On Separate Paths: The Mexican American and African American Legal Campaigns against School Segregation. American Journal of Education, 121(1), 29–55. JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.1086/678124

- Powers, J. M., & Patton, L. (2008). Between Mendez and Brown: “Gonzales v. Sheely” (1951) and the Legal Campaign against Segregation. Law & Social Inquiry, 33(1), 127–171. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20108751

- Ramirez, M. (2025). Court Documents. Mendez et al. v Westminster. https://mendezetalvwestminster.com/court-documents-3/

- Robbie, S. (Director). (2003). Mendez v. Westminster: For All the Children [Video recording]. KOCE-TV. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F46Mlzt2tFc

- Russian, A. (2020, September 15). Sylvia Mendez and Her Parents Fought School Segregation Years Before “Brown v. Board.” Biography. https://www.biography.com/activists/sylvia-mendez-school-segregation-fight

- Saenz, T. A. (2004). Mendez and the Legacy of Brown: A Latino Civil Rights Lawyer’s Assessment. Berkeley La Raza Law Journal, 15, 67–73. https://www.nycourts.gov/ip/judicialinstitute/The_Latino_Judges_Association/pdfs/7.%20Mendez%20and%20the%20Legacy%20of%20Brown..pdf

- Westminster Historical Society. (1944). Hoover School on Olive Street, Westminster, 1944 [Photograph]. Orange County Public Libraries. https://cdm16838.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16838coll1/id/3168

- Wollenberg, C. (1974). Mendez v. Westminster: Race, Nationality and Segregation in California Schools. California Historical Quarterly, 53(4), 317–332. JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.2307/25157525

- Yoerger, Y., & Maher, R. (2007, September 13). Mendez v. Westminster Commemorative Stamp. United States Postal Service. https://about.usps.com/news/national-releases/2007/sr07_038bkgrnd.htm

Cover Photo: Collage featuring Photo of Felícitas and Gonzalo Mendez; Photo of Sylvia Mendez; Copy of Mendez v. Westminster Petition.