Emily Roebling, Engineer of the Brooklyn Bridge

Hidden Voices began as a collaboration between the NYC Department of Education and the Museum of the City of New York that was initiated to help City students learn about the countless individuals who are often “hidden” from traditional historical records. Each of the people highlighted in this series has made a positive impact on their communities while serving as outstanding examples of leadership, advocacy, and community service.

Today, we’re highlighting Emily Roebling, the devoted wife who became the acting engineer of the largest transportation project ever conceived and constructed up until that point in time.

Emily Warren Roebling (1843–1903) is an important figure in New York City’s history both because of who she was and who she wasn’t.

Born in Cold Spring, NY as the second youngest of 12 children, Emily demonstrated early on in her life a love and aptitude for learning. As a teenager, she attended Georgetown Academy of the Visitation (now known as Georgetown Visitation Preparatory School) in Washington D.C., where she studied subjects like history, astronomy, French, and algebra, among others. There, she also discovered an appreciation for engineering and architecture—remarkable at the time because women did not (or were not allowed to in many cases) pursue an education.

Fortunately for Emily, her family, including her eldest brother, Gouverneur, supported Emily’s education and interests. In 1864, during the U.S. Civil War, Gouverneur, who at the time was the commander of the U.S. Fifth Army Corps, invited Emily to his headquarters to meet with his team of Army engineers. Among the elder brother’s team was Washington Roebling, civil engineer and son of the renown suspension bridge engineer, John A. Roebling. It wouldn’t take long for Emily and Washington to find one another—both admired each other’s intelligence, hunger for knowledge, and appreciation for engineering principles, and by January 1865, the two had married.

Building the ‘Eighth Wonder of the World’

By 1860, Brooklyn had become the third largest city in the country, and with only the East River separating it from Manhattan, travel between the two cities was commonplace. Unfortunately, the only way for commuters to travel to Manhattan at the time was through ferries, which were often overcrowded and dangerous. Civil planners had often talked about the possibility of constructing a bridge between the two cities, but the East River itself presented its own challenge: at the time, the turbulent East River was home to the country’s busiest port—any bridge that spanned the river would have to be built over swirling waters and not interfere with the nation’s commercial traffic.

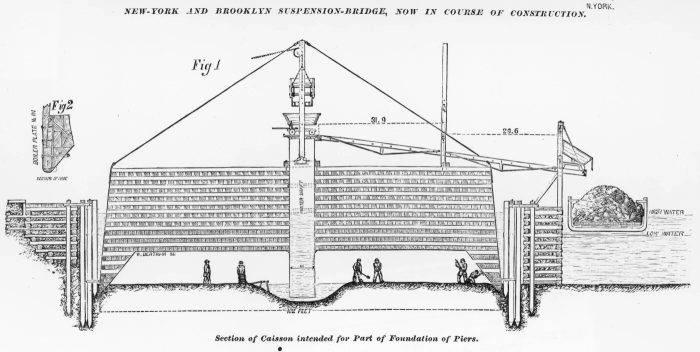

In 1867, John A. Roebling came up with idea of building a suspension bridge held hundreds of feet above the river by steel cables anchored to two huge towers whose foundations would need to be placed down beneath the sediment of the East River. To build these foundations, the elder Roebling determined that caissons, or watertight retaining structures, were required to allow workers to work under the East River. And so that year, Washington and Emily decided to support the elder Roebling’s project and traveled to Europe to learn more about caisson construction and implementation from other engineers.

Unfortunately, John Roebling would never see his project break ground—while scouting areas of the East River for potential bridge development, the elder Roebling suffered a horrible accident in which his foot was crushed by a ferry—he soon developed tetanus and died shortly thereafter. Washington, a talented engineer in his own right, soon took over his father's project in 1869 as its new chief engineer and kicked off the bridge's construction in accordance with his father's plans. Almost a week into the project however, Washington developed decompression sickness, or "the bends," and became bedridden after trying to address air pressure issues with the caissons that were being constructed for the bridge's foundation. The condition left Washington partially paralyzed, blind, deaf, and mute, according to reports at the time, and the project's fate hung in the balance.

With Washington unable to leave his living quarters, Emily stepped up in her husband’s stead and became the driving force moving the project forward. Initially serving as her husband’s secretary— taking notes from him about what needed to be done next— she soon assumed command of the project in all but name, negotiating supply materials, overseeing contracts, addressing labor strife, and acting as a liaison between her bedridden husband and the bridge’s board of trustees. According to one biography, Emily became a kind of “surrogate chief engineer” who used her “superb diplomatic skills” to manage competing parties.

However, despite her knowledge, intelligence, skill, and rapport with the bridge’s construction teams, Emily had to maintain the appearance of her husband’s full control over the project—Washington was at risk of being removed from the project due to his health challenges, so in order to keep Washington from being ousted as chief engineer, Emily helped to sell the idea that the project was proceeding “under the watchful eye” of Washington Roebling himself. Emily deftly argued that Washington was more than capable enough to manage the project from his bedroom window with binoculars in hand and Emily by his side. In truth, however, Washington was in no condition to oversee the day-to-day operations of the project, leaving Emily in sole charge of constructing the bridge as its de-facto engineer. And while it pained her to know that her husband would receive full credit for the years of work that she put into the project, she still took pride in the idea that the Brooklyn Bridge would always be associated with the name “Roebling” thanks to her efforts.

In 1883, after 13 grueling years of construction, Emily Roebling would be the first person to cross the newly-opened Brooklyn Bridge. Throughout the bridge’s opening ceremony, many politicians of the day thanked John and Washington Roebling for their contributions to the project, though no one, save for Congressman Abram Stevens Hewitt (later known as the “father of the NYC subway system,”), recognized Emily’s efforts by name. The bridge, he said, was “an everlasting monument to the sacrificing devotion of a woman and of her capacity for that higher education from which she has been too long disbarred.” Others only hinted at her remarkable contributions, including the New York Times, which slyly declared that “no one man can be given credit of this colossal undertaking.”

Fifteen years later, in an 1898 letter to her son, John, Emily wrote: “I have more brains, common sense and know-how generally than any two engineers, civil or uncivil, and but for me the Brooklyn Bridge would never have had the name Roebling in any way connected with it!”

After the completion of the bridge, Emily Roebling would spend the rest of her life advocating for women’s rights, even going so far as to earn a law degree from New York University and begin speaking publicly in support of equality in marriage. Sadly, Emily would not live long enough to continue this work—on February 28, 1903, she passed away from stomach cancer.

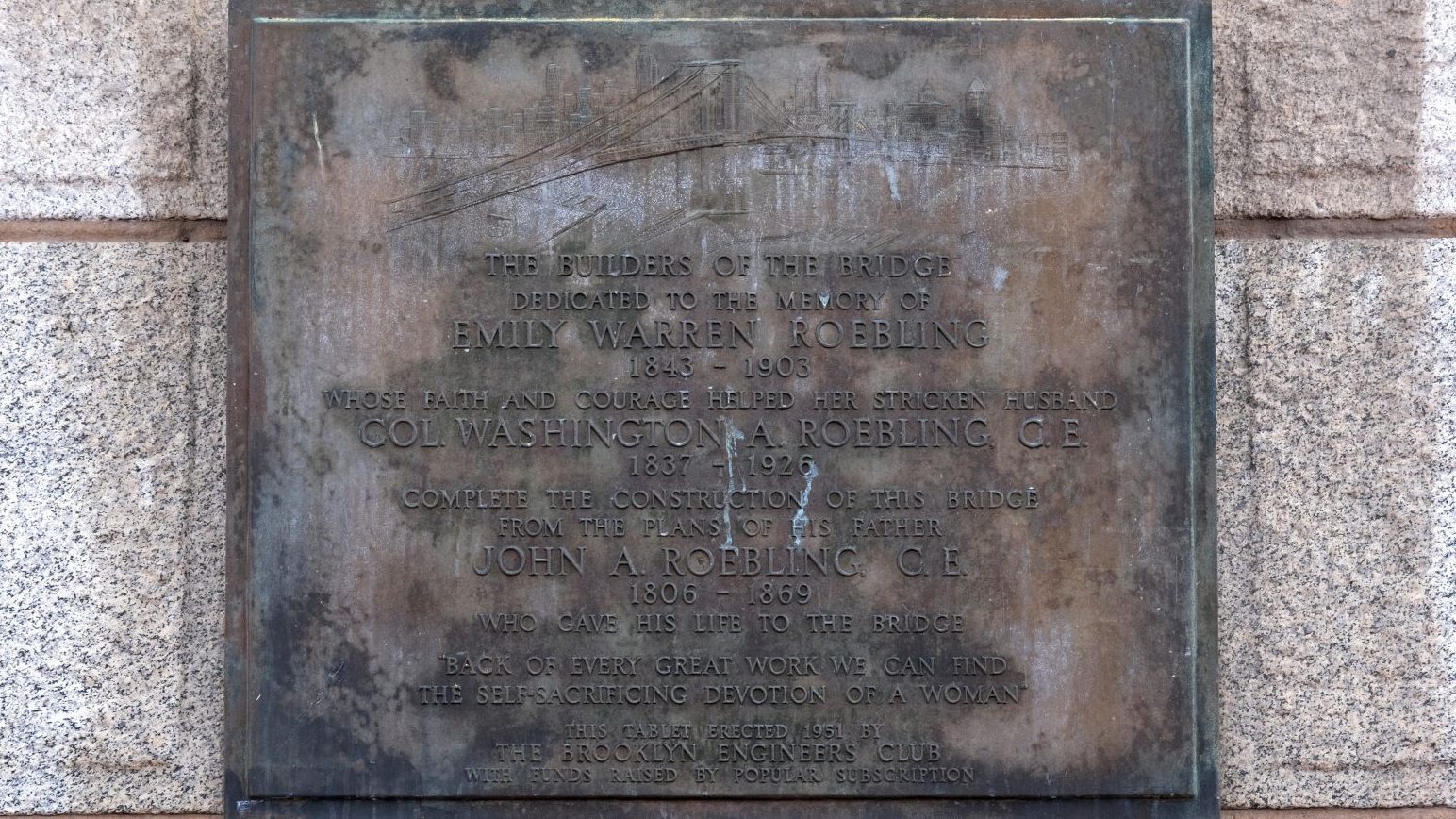

Today, there is a plaque on the Brooklyn Bridge that honors all three Roeblings, especially Emily—”In the back of every great work, we can find the self-sacrificing devotion of a woman.”

Sources

- Bennett, Jessica. “Overlooked: Emily Warren Roebling.” The New York Times, 2018. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/obituaries/overlooked-emily-warren-roebling.html

- Betancourt, Marian. Heroes of New York Harbor: Tales from the City’s Port, Globe Pequot, 2016

- Wagner, Erica. Chief Engineer: Washington Roebling, The Man Who Built the Brooklyn Bridge, Bloomsbury, 2016.

- “Emily Warren Roebling.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emily_Warren_Roebling

- “Emily Warren Roebling: Unsung Hero of the Brooklyn Bridge.” Hidden Voices: Untold Stories of New York City History, NYC Department of Education, 2019, pgs. 59–64

Banner photo by the Hulton Archives/Getty Images. Used under Creative Commons license. Original can be found online.