Fighting for Women’s Health—Dr. Helen Rodríguez-Trías

Hidden Voices began as a collaboration between the NYC Department of Education and the Museum of the City of New York that was initiated to help City students learn about the countless individuals who are often “hidden” from traditional historical records. Each of the people highlighted in this series has made a positive impact on their communities while serving as outstanding examples of leadership, advocacy, and community service.

Today, we’re telling the story of Dr. Helen Rodríguez-Trías, a doctor and activist who played a pivotal role in the women’s health movement by advocating for the rights and freedoms of Latina women and other marginalized communities throughout her career.

Dr. Helen Rodríguez-Trías (1929-2002) was a pediatrician and public health leader who advocated for women’s rights and reproductive freedoms. She would go on to become the first Latina leader of the American Public Health Association and was best known as a champion of health equity for women, people of color, and other marginalized groups.

Helen Rodríguez-Trías was born in 1929 in New York City to Puerto Rican parents. Her family moved back to Puerto Rico shortly thereafter, and she spent most of her early childhood years living there. At 10 years old, however, she returned New York City with her mother where she came face-to-face with bias and discrimination. This was particularly a problem for her at school, where, despite having good grades and being fluent in English, Rodríguez-Trías was placed in less-advanced classes due to embedded prejudices against Latinos that were all too common at the time.

Despite the challenges she faced at a young age, Rodríguez-Trías would go on to attend the University of Puerto Rico in San Juan to pursue a career in medicine, which she once said “combined the things [she] loved the most, science and people.” It was at the university where she first became involved in activism, joining the active Puerto Rican independence movement. Later, she would complete her M.D. program there as well, graduating with highest honors in 1960—the same year she gave birth to her fourth child. After completing her pediatrics residency, she went on to teach at the University Hospital in San Juan, where she established the island’s first infant health clinic. The clinic’s opening impressively resulted in a fifty percent decline in infant mortality at the hospital in only three years.

In 1970, she returned to New York once again and became the director of the pediatrics department at Lincoln Hospital in the South Bronx, which mostly served Black and Latino community members. In the same year that Dr. Rodríguez-Trías started there, a Puerto Rican civil rights organization called the Young Lords staged an occupation of the hospital to demand better quality of care for the mostly Black and Latino patients that were served there at the time. In her position, Rodríguez-Trías helped improve relationships with the South Bronx community by training her staff members to serve their patients’ direct needs and by working with activist groups and civil rights organizations towards the shared goal of ensuring that all patients received adequate, high-quality health care.

Her experiences advocating for the Puerto Rican community in the Bronx prompted Dr. Rodríguez-Trías to focus more on the connections between poor health outcomes and the poverty, inequality, and racism that people were facing regularly in her neighborhood at the time. Throughout the 1970s, she extended her work to the growing women’s health movement, with particular attention towards the decades-long practices of forced and coerced sterilization of women of color.

In her research, Rodriguez-Trías discovered that between the late 1930s and the late 1960s, approximately one third of Puerto Rican women of childbearing age had been sterilized, often having been misled into thinking the procedure was reversible. Studies uncovered that the practice was subsidized by the Puerto Rican government, but also that the issue of coerced sterilization was not unique to the island. In fact, further research revealed that hospitals in the United States were specifically and aggressively targeting patients who were low-income women of color for sterilization procedures. By the mid-1970s, data shows that over 65 percent of sterilizations in U.S. hospitals were being performed on women of color. Rodríguez-Trías once noted that, “While young white middle class women were denied their requests for sterilization, low-income women of certain ethnicity were misled or coerced into them.” She did not hesitate to point out that there was a clear double standard when it came to the reproductive health care options for marginalized women and decided to dedicate her career to fighting these inequities.

Around this time, Dr. Rodríguez-Trías joined with other public health advocates create the Committee to End Sterilization Abuse. In both this organization and later, as a founder of another group called the Committee for Abortion Rights and Against Sterilization Abuse, Rodríguez-Trías led advocacy efforts for free birth control, educated the public about coerced sterilization, and pursued legal and legislative action against the injustices women of color had been facing in the healthcare system. In 1979, the work of these organizations led to the implementation of federal guidelines on sterilization that required written and informed consent and a 30-day waiting period—rules that are still in place to this day.

Throughout her involvement in the women’s health movement, Helen Rodríguez-Trías centered women of color, and particularly Latina women in her work and research. She once said that though she found the movement itself to be diverse, that “the more public positions articulated by the movement didn’t include the experiences or concerns of women of color or of poor women.” However, she and other advocates insisted: “If we’re going to have a movement, it has to be about equity,” a principle that she would keep fighting for as she continued her activism later in her career.

In 1988, Dr. Rodríguez-Trías became the medical director of the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute. She took on this role after her experiences working with HIV-infected women and children made her realize that that the disease was not being adequately addressed by the medical community nor the public. During her tenure, she helped raise awareness of the impact that HIV/AIDS had on families and established standards of care for people with the illness that, after being implemented in New York State, became a model for the rest of the country and improved health care for thousands of people nationwide.

Rodríguez-Trías’s efforts to improve health outcomes for women and people of color throughout her career led her to join her colleagues in creating both the Women’s Caucus and the Latino Caucus of the American Public Health Association, an organization that she would come to lead when she was elected to be their first Latina President years later in 1993. In this role, she urged doctors and public health officials to improve how they address the health care needs of disadvantaged communities, including low-income families, the uninsured, women of color, and people with HIV/AIDS. She used her platform to spread this message across the country and called for health equity, reproductive freedom, and women’s rights nationwide.

In recognition of her important work, Dr. Rodríguez-Trías received the Presidential Citizens Medal from Bill Clinton in January 2001. She passed away in 2002 at age 72 from lung cancer.

Whether it was her work in Puerto Rico and the Bronx as a pediatrician, or across the United States as a leader in the women’s health movement, Dr. Helen Rodríguez-Trías made an enormous impact on the lives of countless individuals. She understood the connections between race, class, and gender to public health outcomes, and she worked to ensure that all individuals received the quality care they deserved. “We cannot achieve a healthier us,” she once explained, “without achieving a healthier, more equitable health care system, and ultimately, a more equitable society.”

Sources

- “Dr. Helen Rodríguez-Trías.” U.S. National Park Service. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/people/dr-helen-rodr%C3%ADguez-tr%C3%ADas.htm

- “Helen Rodríguez-Trías.” Changing the Face of Medicine. Available online: https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_273.html

- Herrera, J.F. Portraits of Hispanic American Heroes. Dial Books for Young Readers, 2014.

- McKiernan-González, J. “American Latino Theme Study: Science.” U.S. National Park Service. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/articles/latinothemescience.htm

- Null, G., and Seaman, B. For Women Only! Your Guide to Health Empowerment. Seven Stories Press, 1999

- Porter, T. “Who Was Helen Rodríguez-Trías? Facts and Quotes from Healthcare Activist Celebrated in Google Doodle.” Newsweek, 7 July, 2018. Available online: https://www.newsweek.com/who-was-helen-rodriguez-trias-facts-and-quotes-healthcare-activist-celebrated-1012919

- Ribas, M. and Rodríguez, N. “Guide to the Helen Rodríguez-Trías Papers, 1929–2002.” Archives of the Puerto Rican Diaspora, Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños at Hunter College, 2007. Available online: https://centropr-archive.hunter.cuny.edu/sites/default/files/faids/rodriguez_triasb.html

- Saxon, W. “Helen Rodríguez-Trías, 72, Family Health Care Advocate.” The New York Times, 4 January, 2002, pg. C11. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2002/01/04/us/helen-rodriguez-trias-72-family-health-care-advocate.html

- Wilcox, J. “The Face of Women’s Health: Helen Rodríguez-Trías.” American Journal of Public Health, 2002, pgs. 92(4), 566–569. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.92.4.566

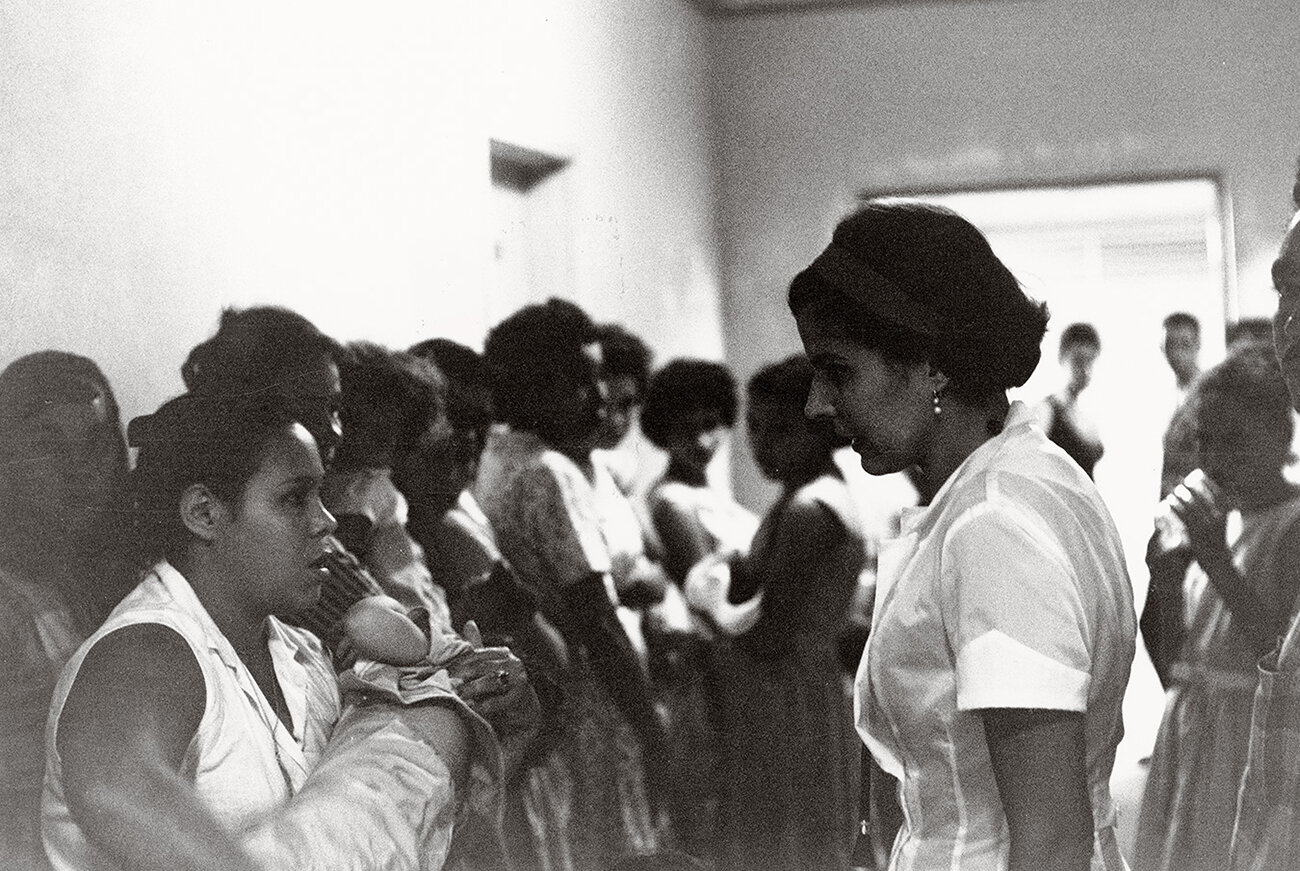

Banner photo by Rafael Pesquera. Used under Creative Commons license. Original can be found on the National Institutes of Health website.