When Edie Met Thea—A New York Love Story

Hidden Voices began as a collaboration with the Museum of the City of New York that was initiated to help City students learn about the countless individuals who are often “hidden” from traditional historical records. Each of the people highlighted in this series has made a positive impact on their communities while serving as outstanding examples of leadership, advocacy, and community service.

Today, we’re sharing the story of Edith “Edie” Windsor, a computer programmer and pioneering LGBTQ+ activist best known for her role in the landmark Supreme Court case, United States v. Windsor, that helped lead towards the eventual legalization of gay marriage in the United States.

“Is your dance card full?”

When Edie Windsor walked into a restaurant in Greenwich Village on the night she would first meet Thea Spyer in 1963, she could not have known that 50 years later, a Supreme Court case bearing her name would catapult her to national fame. And yet, on June 26, 2013, a decision was made in United States v. Windsor that would change thousands of lives, and earn Edie national hero status among thousands of LGBTQ+ people in the United States.

Edith Schlain was born to Russian Jewish immigrants in Philadelphia in 1929, and grew up there during the height of the Great Depression. But by the time she met Thea, the woman and clinical psychologist who would later become her partner, Edie had already been living in New York for several years, having pursued her master’s degree in mathematics at New York University in 1955.

She had also been briefly married to a man named Saul Windsor, whom she separated from in 1952 after less than a year of marriage. “I told him the truth,” Edie later recalled in an interview. “I said, ‘Honey, you deserve a lot more. You deserve somebody who thinks you’re the best, because you are. But I need something else.'”

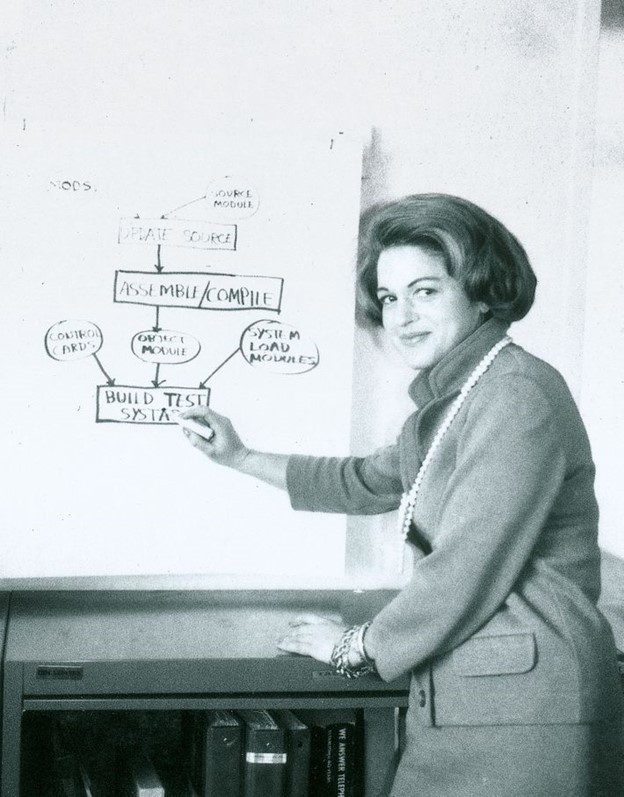

She completed her studies in 1957 and got a job as a research assistant with the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. This was no small feat: not only was Windsor working in a male-dominated field, but she also applied to the position during the height of the Lavender Scare—a period during which thousands of gay employees were fired or forced to resign from their jobs with the federal government due to the unfounded fear that their sexuality meant they were vulnerable to blackmail, and thus posed a threat to national security. Edie’s job, which involved programming an eight-ton UNIVAC computer, required her to interview with the FBI to obtain a security clearance. Windsor was nervous that the FBI would discover her sexuality and that she would lose the opportunity. And so, in her attempt to remain undetected, she said she “went to the interview in high heels and a dress with crinolines.”

She passed the interview and got the job, but she would never be able to be open about her personal relationships while working there. That would remain the case for many years, including when Windsor was later hired in 1958 as a programmer at IBM, and worked her way up to become a Senior Systems Programmer, the highest possible technical ranking at the company.

As her career took off, so too, did her relationship with Spyer. “We immediately just fit—our bodies fit,” recalled Spyer in a later interview. The couple got engaged in 1967, when Spyer proposed with a brooch—a circle of diamonds—instead of an engagement ring, which would have prompted too much curiosity among Edie’s coworkers.

At the time they got engaged, same-sex marriage was impossible virtually anywhere, and so they waited. In the meantime, they became more active in the growing LGBTQ+ rights movement, and eventually, they became one of the first couples to enter into a domestic partnership in New York state, registering as soon as it became possible to do so in 1993.

Unfortunately, just as it seemed like progress was being made, Congress passed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which President Bill Clinton later signed into law. DOMA explicitly defined marriage for the purposes of federal legal recognition as a union between a man and a woman only, but left it up to the states to decide whether they wished to grant marriage licenses to same-sex couples. The House Judiciary Committee issued a report at the time in favor of the law that made their reasoning clear: they argued that DOMA was necessary because it reflected what they referred to as a “collective moral judgement” that “heterosexuality better comports with traditional… morality.” DOMA enshrined these discriminatory beliefs into law, ensuring that same-sex couples would not receive the same benefits and privileges from the federal government as heterosexual couples did.

In 2007, Windsor would experience for herself the disparities that DOMA created: Spyer—who had been previously diagnosed with multiple sclerosis since 1977—was in declining health, and Windsor had retired to become her fulltime caregiver. With DOMA still in effect in the United States, and gay marriage not yet legalized in New York, the couple decided to get married in Canada. By this point, New York State recognized same-sex marriages performed elsewhere, so though the state would not yet grant them a license themselves, it would consider their marriage in Toronto to be valid.

Sadly, Spyer passed away in 2009, within a year and a half of their wedding day. Because of DOMA, Edie was not entitled to the same federal benefits as other widows, since she and Thea were both women. Though she would not have been responsible for paying estate taxes had she been married to a man, she instead discovered that because she had a female partner, she was expected to pay over $360,000 in taxes to be able to inherit Spyer’s estate. In fact, legally speaking, it was as though Edie and Thea were strangers instead of family.

Edie realized this treatment was both unfair and unacceptable, so she went to court, hoping to prove it was unconstitutional as well. She once said in an interview about her decision to take up the fight for marriage equality, “It’s heartbreaking,” that she had been put into such a position. “It’s just a terrible injustice, and I don’t expect that from my country. I think it’s a mistake that has to get corrected.”

“Like countless other same-sex couples, we engaged in a constant struggle to balance our love for one another and our desire to live openly and with dignity on the one hand, with our fear of disapproval and discrimination on the other.”

—Edith Windsor

After a long fight, it finally would: in 2012, a judge in New York ruled in Edie’s favor, and a year later, the Supreme Court agreed: in a 5-4 decision, DOMA was declared unconstitutional, meaning in the places where gay marriage was already legalized—which included twelve states plus Washington, D.C. at the time of the ruling—that same-sex couples would finally be provided with the same benefits that were given to other couples. In addition to estate tax, this included things like same-sex couples’ ability to adopt a child, their social security benefits, their right to sponsor their spouse for a green card, and so much more.

That same year, Edie was honored as the Grand Marshal of New York City’s 2013 Pride March in recognition of her hard-won fight for equality. She was also the runner-up for Time’s 2013 Person of the Year recognition—an indication of just how important this case was at the time.

It would take a few more years—until the Supreme Court issued their opinion in Obergefell v. Hodges exactly two years after the Windsor decision, in 2015—for gay marriage to be made legal throughout the entire United States. Then in 2022, President Biden signed the Respect for Marriage Act into law, another step forward on the long road towards marriage equality which further enshrined it into U.S. law. None of it would have been possible without Edie’s courageous fight.

Windsor died in 2017 at 88 years old, but her legacy lives on every time an LGBTQ+ couple says “I Do,” and she was proud of what her case had achieved: “If you have to outlive a great love,” she once said, “I can’t think of a better way to do it than being everybody’s hero.”

Today, Edie Windsor is fondly remembered for her advocacy on behalf of LGBTQ+ rights and her place in history: in 2022, the New York City Council designated the corner of Fifth Avenue and Washington Square North, where she lived with Thea for over 40 years, as “Edie Windsor and Thea Spyer Way.”

You can learn more about Edith Windsor and other trailblazers like her through through our “Hidden Voices” series, as well as through our classroom-based “Hidden Voices: LGBTQ+ Stories in United States” curriculum guide on WeTeach.

Sources

Adkins, J. (2016, August 15). “These People Are Frightened to Death”—Congressional Investigations and the Lavender Scare. Prologue Magazine, 48(2). https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2016/summer/lavender.html

Biden, J. R., & Harris, K. (2022, December 13). Remarks by President Biden and Vice President Harris at Signing of H.R. 8404, the Respect for Marriage Act [Speech]. The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2022/12/13/remarks-by-president-biden-and-vice-president-harris-at-signing-of-h-r-8404-the-respect-for-marriage-act/

Canady, C. (1996). Defense of Marriage Act: Report to Accompany H.R. 3396 (104–664; 104th Congress, Second Session). United States House of Representatives Committee on the Judiciary. https://www.congress.gov/congressional-report/104th-congress/house-report/664/1

Dwyer, C. (2017, September 12). Edith Windsor, LGBTQ Advocate Who Fought the Defense of Marriage Act, Dies At 88. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/09/12/550502373/edith-windsor-lgbtq-advocate-who-fought-the-defense-of-marriage-act-dies-at-88

Ellis, S. K. (2017, September 20). GLAAD President Reflects on Edie Windsor’s Impact on LGBTQ Community. Variety. https://variety.com/2017/voices/columns/glaad-edie-windsor-lgbtq-1202563945/

Fairyington, S. (2014, February 14). Inside the Love Story That Brought Down DOMA. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2014/02/inside-the-love-story-that-brought-down-doma/283840/

Frankel, J. (2017, September 14). Edie Windsor, LGBT Activist, Was Also a Computer Whiz. Newsweek. https://www.newsweek.com/lgbt-activist-edith-windsor-same-sex-marriage-pioneer-computer-genius-664818

Gray, E. (2013, December 11). Runner-Up: Edith Windsor the Unlikely Activist. Time. https://poy.time.com/2013/12/11/runner-up-edith-windsor-the-unlikely-activist/2/

Greer, A. S. (2020). We Love You, Edie Windsor! In M. Chabon & A. Waldman (Eds.), Fight of the Century: Writers Reflect on 100 Years of Landmark ACLU Cases (pp. 302–308). Simon & Schuster.

Hajela, D., & Peltz, J. (2017, September 13). Edith Windsor, who led the way to legalizing same-sex marriage, dies. SFGate. https://www.sfgate.com/news/article/Edith-Windsor-who-led-the-way-to-legalizing-12195740.php

Hamburg Coplan, J. (2011, Fall). When a Woman Loves a Woman. The New York University Alumni Magazine, Fall 2011(17), 38–41. https://alumnimagazine.nyu.edu/issue17/17_FEA_DOMA.html

Haynes, S. (2020, December 22). The Anti-Gay “Lavender Scare” Is Rarely Taught in Schools. Time. https://time.com/5922679/lavender-scare-history/

Hidden Voices: LGBTQ+ Stories in United States History. (2021, March). New York City Department of Education. https://www.weteachnyc.org/resources/resource/hidden-voices-lgbtq-stories-in-united-states-history-lesson-plans-Public-facing/

Kleeman, S. (2013, June 26). Plaintiff In DOMA Lawsuit: “Internalized Homophobia Is a Big Bitch.” Gothamist. https://gothamist.com/news/plaintiff-in-doma-lawsuit-internalized-homophobia-is-a-big-bitch

Landsbaum, C. (2017, September 12). Edith Windsor, Whose Historic Supreme-Court Case Paved the Way for Same-Sex Marriage, Dies At 88. The Cut. https://www.thecut.com/2017/09/edith-windsor-same-sex-marriage-advocate-obituary.html#_ga=2.123422603.1825119106.1687268667-1074093144.1687268667

Langmuir, M. (2013, March 17). Edith Windsor’s Pioneering Life, From Portofino to the Supreme Court. New York Magazine, March 25, 2013. https://www.thecut.com/2013/03/gay-rights-pioneer-edith-windsor.html

Levy, A. (2013, September 23). The Perfect Wife. The New Yorker, September 30, 2013. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/09/30/the-perfect-wife

Marder, J. (2015, June 26). “It is so ordered.” Supreme Court Justices on gay marriage decision. PBS NewsHour. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/ordered-scotus-gay-marriage-decision

McBride, B. (2017, June 26). Four Cases That Paved the Way for Marriage Equality and a Reminder of the Work Ahead. Human Rights Campaign. https://www.hrc.org/news/four-cases-that-paved-the-way-for-marriage-equality-and-a-reminder-of-the-w

Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. ___ (U.S. Supreme Court 2015). Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit https://www.oyez.org/cases/2014/14-556

Saltonstall, G. (2022, July 15). West Village Block Named After Couple Who Won Gay Marriage Rights. West Village, NY Patch. https://patch.com/new-york/west-village/west-village-block-named-after-couple-who-won-gay-marriage-rights

Socarides, R. (2017, September 13). The Legacy of Edith Windsor. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/the-legacy-of-edith-windsor

Thea Spyer and Edith Windsor. (2007, May 27). The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/27/fashion/weddings/27spyer.html

Totenberg, N. (2013, March 21). Meet The 83-Year-Old Taking on the U.S. Over Same-Sex Marriage. In All Things Considered. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2013/03/21/174944430/meet-the-83-year-old-taking-on-the-u-s-over-same-sex-marriage

United States v. Windsor, 570 U.S. 744 (U.S. Supreme Court 2013). Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit https://www.oyez.org/cases/2012/12-307

Wex Definitions Team. Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA). Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute. Retrieved from https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/defense_of_marriage_act_(doma)

Banner photo by Edith Windsor. Original can be found on CNN