Eugenie Clark, The 'Shark Lady' Who Took a Bite Out of Marine Biology

Hidden Voices began as a collaboration with the Museum of the City of New York that was initiated to help City students learn about the countless individuals who are often "hidden" from traditional historical records. Each of the people highlighted in this series has made a positive impact on their communities while serving as outstanding examples of leadership, advocacy, and community service.

Today, we're sharing the story of Dr. Eugenie Clark, a fish scientist from New York City who earned herself the nickname, "Shark Lady," thanks to her trailblazing research on fish and shark species around the world as well as her personal dedication to protecting sharks and their ocean habitats from extinction.

Eugenie Clark (1922–2015) spent much of her childhood roaming the old New York Aquarium back when it was located not in Coney Island, but in Battery Park. Housed in the historic Castle Clinton—which had previously served as a defensive fort in the War of 1812, an entertainment center that hosted former presidents, and an immigration facility prior to Ellis Island—the aquarium was one of the most popular attractions in Manhattan.

When the New York Zoological Society took over aquarium operations in 1902, the new management sought out to both entertain and educate the aquarium's visitors, particularly City schoolchildren. As a result, thousands of young students, including Eugenie, were invited to the aquarium and introduced to the wonders of aquatic life.

Born in New York City on May 4, 1922, Eugenie credits both her trips to the aquarium and her Japanese heritage with igniting her interest in ichthyology, or the study of fish. Her mother, Yumico Clark (née Mitomi) was a Japanese American woman who taught Eugenie about the central role the sea has in Japanese culture. Eugenie's interest in the sea—and the creatures who lived there—grew as she advanced through school, including her time as a student at William Cullen Bryant High School in Queens.

She'd eventually turn her interest into a more serious academic pursuit when she enrolled in Hunter College and earned a bachelor's degree in Zoology in 1942. She then continued her education and enrolled at New York University, where she earned a Master's degree in 1946, and a PhD in 1950. Her academic pursuits led to her receiving a Fulbright scholarship in 1950, and later, research positions at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California and the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Throughout her studies, Eugenie was often the only person of Japanese descent, as well as one of only a few women, in her classes. This resulted in several hurdles throughout her career. In 1994, she recalled in an interview:

“When I applied to graduate school at Columbia University, the Chairman of the Zoology Department (a famous geneticist) told me, ‘Well, I guess we could take you but to be honest, I can tell by looking at you, if you do finish you will probably get married, have a bunch of kids, and never do anything in science after we have invested our time in money in you."

Another moment came in 1947, when had been commissioned by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to study animal behavior in the Philippines—unfortunately, she was never able to take on this research work, as she had been detained by the FBI in Hawaii due to World War II-era laws that discriminated against people of Japanese ancestry.

Fortunately, Eugenie did not let these challenges discourage her, and she maintained her dedication to her academic and career-related pursuits. By 1955, Eugenie had been entrusted with setting up the Cape Haze Marine Laboratory. Now known as the Mote Marine Laboratory and relocated to Sarasota, Florida, Eugenie conducted groundbreaking research as the longtime director of the lab, like an experiment in which she trained sharks to press a target to obtain food, proving their intelligence. It was in this role that Clark earned her nickname: The Shark Lady.

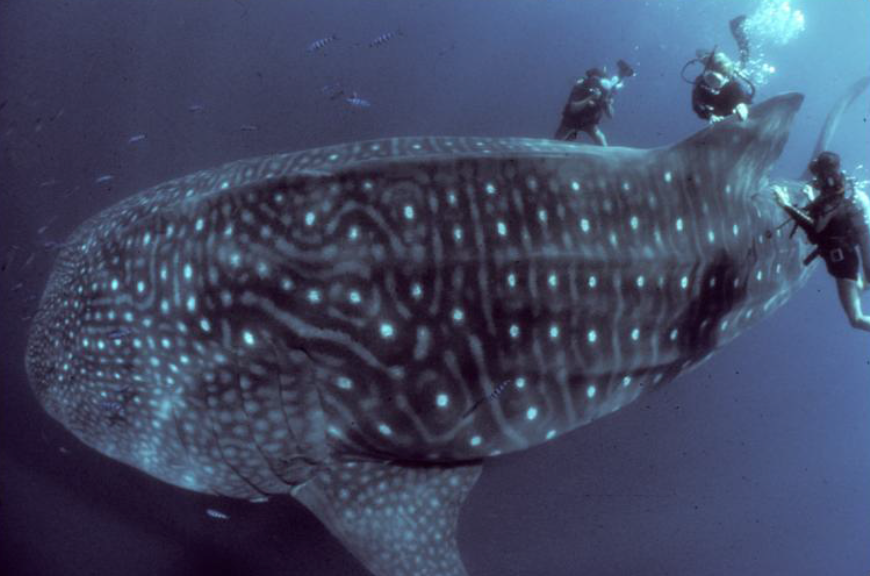

Her research was not confined just to Florida waters, though—Clark traveled around the world to learn as much as she could about different marine species. In a dive off the coast of Mexico, she and her team helped disprove the myth that sharks must keep moving to survive, as they discovered caves where the water was high in oxygen, but low in salinity, and allowed the “sleeping” sharks that lived in those waters to stop and rest.

She also became the first woman to conduct any scientific research in the Red Sea, where her and her team would discover that a native species known as the “Moses sole” could produce a natural shark repellent that protected them from the deadly predators.

Unfortunately for humans, the team’s subsequent experiments proved that the unique chemical was ineffective for protecting divers against potential attacks. However, Clark would have argued that such a thing was mostly unnecessary anyway; despite the common perception of sharks as vicious and dangerous creatures, Eugenie maintained that they had a relatively calm nature: “No creature on earth has a worse, and perhaps less deserved, reputation than the shark,” she wrote in National Geographic in 1981. “During [my] years of research on sharks I have found them to be normally unaggressive and even timid toward man.”

Clark was so unafraid of the sharks she researched in fact, that she not only dove into the waters they called home, but once even rode on the back of a 40-foot long whale shark traveling at over three knots along the coast of California.

Despite these facts, however, it is not surprising that most people view sharks in a negative light; examples of the animals featured in popular media—like the film "Jaws" and the Discovery Channel’s "Shark Week" programming, among other examples—have portrayed sharks as violent human killing machines, despite the reality that they rarely go after humans. This has had a noticeable real-world effect: in the years since "Jaws" premiered, shark populations in the United States have suffered noticeable declines.

Knowing that public perception and conservation efforts are intrinsically linked—traditionally, studies have found “flagship species” that are viewed more positively or considered cuter (like polar bears or pandas) have been favored both as recipients of donations and funding, and as research subjects—Clark dedicated herself to “rebranding” sharks as creatures worthy of saving. Protecting marine life and their habitats was of the upmost importance to Eugenie, and she devoted her life to educating people on the importance of sharks to their ecosystem.

One way that Clark made use of her expert communication skills was as an educator; while she held many teaching positions at different universities throughout her career, the longest by far was at the University of Maryland, where she joined the faculty in 1968, became a full professor in 1973, and where she remained until her retirement in 1992.

Conservation and research truly were lifetime pursuits for Clark: when she died at age 92 in 2015, after having battled lung cancer for several years, her obituary, The New York Times counted that over a nearly 75-year long career she “wrote three books, 80 scientific treatises and more than 70 articles and professional papers; lectured at 60 American universities and in 19 countries abroad; appeared in 50 television specials and documentaries; was the subject of many biographies and profiles; made intriguing scientific discoveries; and had four species of fish named for her.”

To be able to publish all of this work, she made more than 5,000 dives over the course of her life, the last of which took place only a year before she died, in 2014. The long list of awards she received during her lifetime included a Medal of Excellence from the American Society of Oceanographers, a place in the International SCUBA Diving Hall of Fame, and the Legend of the Sea Award from Beneath the Sea, among many others.

In her own words, Clark did not use these statistics to summarize her contributions and legacy, though. Instead, she once wrote, “In total, my popular and scientific articles have helped dispel some of the myths about sharks that are so unfair to sharks, added a piece to the puzzle here and there towards our ultimate understanding about fishes, and inspired young people, especially girls, to study science.”

Sources

Adam, D., & Cole, C. (2010, May 22). Meerkats, chimps, and pandas: The cute and the furry attract scientists’ attention and conservation funding. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2010/may/23/endangeredspecies-conservation

Alfuso, R. (2010, Fall). NYU Alumni Magazine: A Life Under the Sea. NYU Alumni Magazine, #15, 56–57.

Balon, E. K. (1994a). An interview with Eugenie Clark. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 41(1), 121–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02197840

Balon, E. K. (1994b). The life and work of Eugenie Clark: Devoted to diving and science. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 41(1), 89–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02197838

Clark, E. (1969). The Lady and the Sharks. Harper Collins.

Clark, E., & Doubilet, D. (1974, November). The Red Sea’s Sharkproof Fish. National Geographic, 146, 718–727. National Geographic Society.

Clark, E., & Doubilet, D. (1975, April). Into the Lairs of “Sleeping” Sharks. National Geographic, 147, 570–584. National Geographic Society.

Clark, E., & Doubilet, D. (1981, August). Sharks: Magnificent and Misunderstood. National Geographic, 160, 138–186. National Geographic Society.

Clark, E., & Doubilet, D. (1992, December). Whale Sharks, Gentle Monsters of the Deep. National Geographic, 182, 121–139. National Geographic Society.

Dang, J. (2017, September 27). Favoring One Over the Other: Bias in Animal Conservation. Writing in the Natural Sciences, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://writingscience.web.unc.edu/2017/09/favoring-one-over-the-other-bias-in-animal-conservation/

Digital Museum of the History of Japanese in NY. (2022, October 21). Dr. Eugenie Clark Centennial. Digital Museum of the History of Japanese in NY. https://www.historyofjapaneseinny.org/blog/artifacts/dr-eugenie-clark-centennial/

Doubilet, A. (2015, March 5). Dr. Eugenie Clark, “The Shark Lady.” Academy of Underwater Arts & Sciences. https://www.auas-nogi.org/single-post/2015/03/05/dr-eugenie-clark-the-shark-lady-by-anne-doubilet

Duncan, J. (2001). Eugenie Clark. In Ahead of Their Time: A Biographical Dictionary of Risk-Taking Women. ABC-CLIO, LLC.

Eilperin, J. (2011, June). Swimming With Whale Sharks. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/swimming-with-whale-sharks-160147604/

Eugenie Clark. (2024). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Eugenie_Clark&oldid=1193139820

Gallagher, A. (2018, March). Eugenie Clark—The Shark Lady. Smithsonian Ocean. https://ocean.si.edu/ocean-life/sharks-rays/eugenie-clark-shark-lady

Graehling, S. (2022, March 10). Eugenie Clark: The Shark Lady. WCS Wild View. https://blog.wcs.org/photo/2022/03/10/eugenie-clark-the-shark-lady-sea-lion-womens-history-month/

Gwin, P. (2021, July). Bonus episode: The surprising superpowers of sharks. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/podcasts/article/bonus-episode-the-surprising-superpowers-of-sharks

Hoyt, A. (2017, April 17). How Charismatic Megafauna Work. HowStuffWorks. https://animals.howstuffworks.com/endangered-species/charismatic-megafauna.htm

McFadden, R. D. (2015, February 26). Eugenie Clark, Scholar of the Life Aquatic, Dies at 92. The New York Times, 12.

Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium. (2023, January 5). Explore the Life of Dr. Eugenie Clark. Dr. Eugenie Clark. https://sites.google.com/mote.org/eugenie-clark/explore

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2015). Dr. Eugenie Clark (1922-2015). National Ocean Service. https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/news/may15/eugenie-clark.html

Reynolds, E. (2016, March 23). Funding for endangered animals is “unevenly distributed.” WIRED. https://www.wired.com/story/conservation-animal-inequality/

Romeo, J. (2020, August 14). Sharks Before and After Jaws. JSTOR Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/sharks-before-and-after-jaws/

Rutger, H. (2015, March 5). Remembering Mote’s “Shark Lady”: The Life and Legacy of Dr. Eugenie Clark | News & Press. Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium. https://mote.org/news/article/remembering-the-shark-lady-the-life-and-legacy-of-dr.-eugenie-clark

Staff Report. (2015, February 25). Timeline: Eugenie Clark’s life and work. Sarasota Herald-Tribune. https://www.heraldtribune.com/story/news/2015/02/26/timeline-eugenie-clarks-life-and-work/29301086007/

Stone, A. (2015, February 25). “Shark Lady” Eugenie Clark, Famed Marine Biologist, Has Died. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/article/150225-eugenie-clark-shark-lady-marine-biologist-obituary-science

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. (1917). The Aquarium, New York City. Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e2-8aeb-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

The National WWII Museum. Japanese American Incarceration. The National WWII Museum in New Orleans. Retrieved from https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/japanese-american-incarceration

U.S. National Park Service. (2023, August 8). History & Culture—Castle Clinton National Monument. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/cacl/learn/historyculture/index.htm

U.S. National Park Service. (2024, March 6). Aquarium Era 1896–1941—Castle Clinton National Monument. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/cacl/learn/historyculture/aquarium-era.htm

Veríssimo, D., & Smith, B. (2017, June 27). When It Comes to Conservation, Are Ugly Animals a Lost Cause? Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/are-ugly-animals-lost-cause-180963807/

Wallace, N. (2022, May 4). Eugenie Clark Swam with Sharks and Blazed a Path for Women in Science. Densho: Japanese American Incarceration and Japanese Internment. https://densho.org/catalyst/eugenie-clark-swam-with-sharks-and-blazed-a-path-for-women-in-science/

Banner photo featuring images from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (left), the Academy of Underwater Arts & Sciences (center), Mote Marine Laboratory (sketches on center right), and National Geographic (right).