Lewis H. Latimer Lights the Way

Hidden Voices began as a collaboration with the Museum of the City of New York to help City students learn about the countless individuals who are often “hidden” from traditional historical records. Each of the people highlighted in this series has made a positive impact on their communities while serving as outstanding examples of leadership, advocacy, and community service.

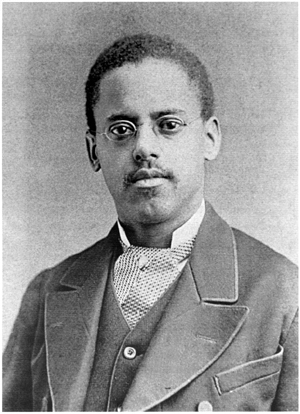

Today, we're sharing the story of Lewis Howard Latimer, who worked alongside some of the most notable inventors of the nineteenth century, achieving great success as a draftsman, patent expert, and inventor in his own right—in particular, contributing to the design of the incandescent lightbulb to make electric lighting more commercially viable.

The nineteenth century was a golden age for invention in the United States; during the late 1800s, patents were filed for Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone, George Eastman’s Kodak camera, Carl Benz’s first gas-powered automobile, and Thomas Edison’s incandescent light bulb. These were groundbreaking inventions that shaped modern society—but it has long been contested that each of these men deserve sole credit for the new technologies they created.

Many scientists and engineers were often working on similar ideas at the same time, or building off of work that others had previously done to make improvements to the commercial viability of these devices. One such inventor was Lewis Howard Latimer, an expert draftsman, an innovator in electric lighting, and a champion for civil rights. As a Black man whose parents escaped enslavement prior to his birth, Latimer overcame incredible obstacles to leave a lasting impact on modern society. His work helped bring electric lighting and the telephone into everyday life, and with one of his patents, even laid the foundation for modern air conditioning.

Lewis Howard Latimer was born on September 4, 1848, in Chelsea, Massachusetts. His parents, George and Rebecca Latimer, were formerly enslaved people who had escaped from Virginia. Their flight to freedom was not easy; when they arrived in Boston, George was recognized, arrested, and nearly sent back to slavery. The case gained national attention, becoming a major event in the abolitionist movement. Eventually, George’s freedom was purchased, and the Latimers were able to start a new life in Massachusetts.

By the time Lewis was twelve, the country was on the brink of civil war. His two older brothers joined the Union armed forces, and when Lewis turned sixteen, he followed in their footsteps. He enlisted in the U.S. Navy, serving aboard the USS Massasoit during the final year of the Civil War. When the war ended, he returned to Boston, eager to find a way to support himself and his family.

He soon found a job as an office boy at a patent law firm in the city called Crosby, Halsted, and Gould. The work fascinated him, particularly the precise drawings made by draftsmen. Without formal training, and having only received an education through grade school, Latimer studied every detail, observing his colleagues and teaching himself mechanical drawing in his free time. His determination paid off. Impressed by his talent, the firm promoted him to draftsman, giving him the opportunity to work directly on patent applications for new inventions.

In 1876, Latimer’s drafting skills led to an opportunity to work with Alexander Graham Bell to complete detailed technical drawings for one of the most important inventions of all time: the telephone. The two men worked together late into the night, racing against the clock to complete the patent application before Bell’s competitors could do the same. Their efforts paid off. Bell’s telephone patent was successfully filed, securing his place in history as the inventor of the telephone.

Latimer’s role in this breakthrough was largely overlooked, but the experience changed his life. It placed him at the center of the rapidly growing field of electrical engineering and opened the door to even greater opportunities.

Just a few years later, Latimer’s career took another leap forward when he moved to Bridgeport, Connecticut. There, he was hired to work as a draftsman at the U.S. Electric Company by Hiram Maxim, who later became famous for inventing the machine gun, but was best known at the time as a competitor of Thomas Edison in the race to develop electric lighting. At the time, lightbulbs were fragile, expensive, and had short lifespans. One of the biggest challenges was creating a filament that would last long enough to make electric lighting practical and commercially viable.

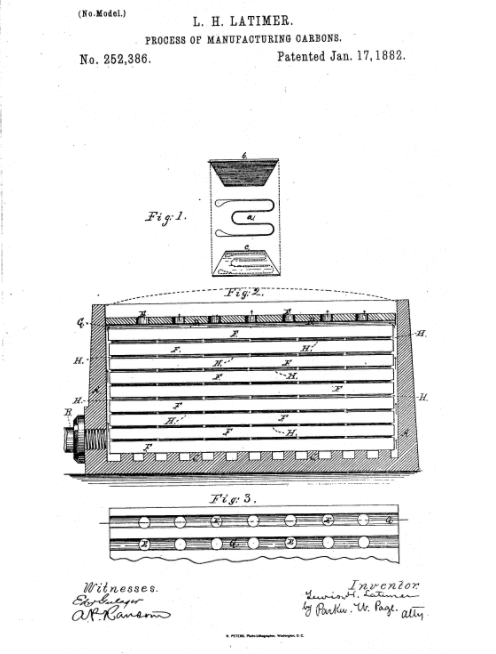

Latimer developed a groundbreaking method to improve the carbon filament used in incandescent bulbs. His innovation made the filaments stronger, longer-lasting, and easier to produce, bringing electric lighting one step closer to widespread use. In 1882, he received a patent for this "Process of Manufacturing Carbons," solidifying his reputation as a brilliant inventor.

When Maxim’s company moved to New York in 1880, Latimer moved with it, and he worked in the field to supervise the installation of some of the world’s first public electric lighting systems in the City, including in the Equitable Building and the Union League Club, among other important buildings. He would later complete similar assignments for the U.S. Electric Company in Philadelphia, Montreal, and finally, in London, where he traveled in 1882 to advise the English in setting up a lamp factory. Despite his expertise, Latimer did not receive a warm welcome in Europe; many of his workers there resisted being under the supervision of a Black man. Reflecting on the discrimination he faced in this role, he wrote that he was “in hot water from the first moment to the end.” In spite of these challenges, at a time when most homes still relied on gas lamps or candles, Latimer nevertheless continued to help usher in the new era of illumination.

By 1884, Latimer had returned to the United States, and his expertise had caught the attention of Thomas Edison, who invited him to join the Edison Electric Light Company. As the only Black engineer on Edison’s team, Latimer worked as a draftsman and patent investigator, helping Edison protect his inventions from legal challenges. His legal expertise became one of his most valuable contributions for Edison’s company, as Edison’s electric light patents faced fierce competition from rival inventors and companies. Latimer played a crucial role in defending them in court. His deep understanding of patent law, combined with his firsthand knowledge of the technology, made him an essential figure in these intense legal battles.

It was during his time working for Edison that Latimer also wrote and published Incandescent Electric Lighting, considered the first book on electric lighting technology, and one that sparked interest even among readers that lacked a scientific background.

While Latimer is best known for his work on the lightbulb, he was a true innovator who developed a range of practical inventions. One of his first patents, awarded in 1874, was for an improved toilet system for railroad cars. He later designed an early air conditioning system, which both cooled and disinfected indoor spaces. In total, he received seven U.S. patents during his life.

Throughout his career, Latimer believed that technology should improve everyday life, and his inventions reflected that philosophy. He also believed in a connection between the sciences and the humanities, and placed great importance on the value of music, literature, and poetry—the latter of which is evident in the way he wrote about his own work: “Like the light of the sun,” Latimer wrote of the incandescent bulb, “it beautifies all things on which it shines, and is no less welcome in the palace than in the humblest home."

Beyond his technical achievements, Latimer was also a passionate advocate for racial equality and education. His commitment to racial justice was undoubtedly influenced by his family’s close ties to the abolitionist movement, as well as his own experiences in the Union Navy. In 1895, he wrote a powerful statement for the National Conference of Colored Men, calling for equal rights, security, and opportunity for Black Americans. He knew that technological progress alone wasn’t enough to advance our society—true progress required social change. Latimer put word to action, working tirelessly within his community to promote education and racial integration, and was dedicated to his volunteer work teaching English and mechanical drawing to immigrants at the Henry Street Settlement in New York, helping them gain valuable skills for better job opportunities.

Latimer spent the final decades of his life in Flushing, Queens, where he continued to be active in his community, including as a founding member of the First Unitarian Church of Flushing, New York. He was also an active member of the Grand Army of the Republic, an organization for American Civil War veterans. In 1918, he was honored as the first and only Black member of the Edison Pioneers, a prestigious group of Edison’s closest collaborators. He remained deeply engaged in the world of invention and continued writing and mentoring young engineers.

Lewis H. Latimer passed away on December 11, 1928, at the age of 80. Although his name has somewhat faded from public recognition, his contributions never stopped shaping the world. His improvements to electric lighting helped make it affordable and practical, his work on the telephone helped revolutionize communication, and his advocacy for civil rights set an example for generations to come.

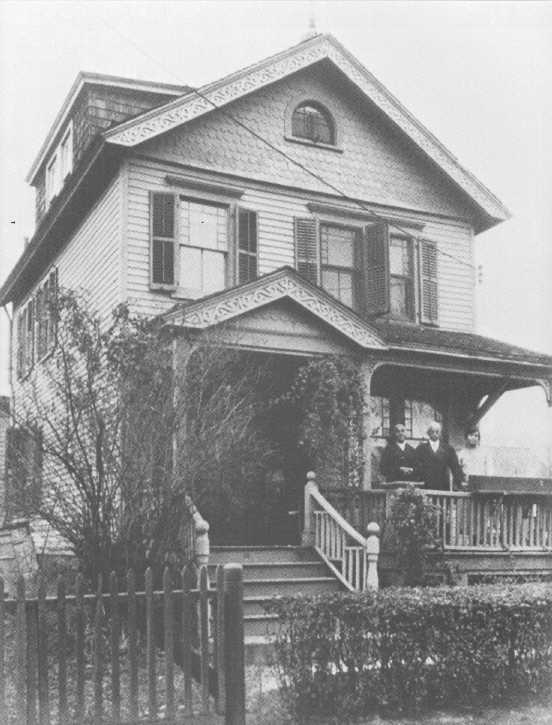

Today, the home in Queens where he lived from 1903 to 1928 with his wife, Mary, and their two daughters has been preserved as the Lewis H. Latimer House Museum, a tribute to his life and work. A school in Brooklyn, P.S. 56 Lewis H. Latimer School, also bears his name, ensuring that his legacy continues to inspire young minds.

Lewis H. Latimer was more than just an inventor—he was a pioneer who helped shape modern technology and fought for a more just society. His life and work are a testament to the power of perseverance, creativity, and the belief that knowledge should be shared for the benefit of all.

Sources

- Biography.com Editors. (2024, February 8). Lewis Howard Latimer—Inventions, Accomplishments & Facts. Biography. https://www.biography.com/inventors/lewis-howard-latimer

- Fouché, R. (2003). Black inventors in the age of segregation: Granville T. Woods, Lewis H. Latimer & Shelby J. Davidson. The Johns Hopkins Univ. Press.

- George, L. (1999, February 1). Innovative Lives: Lewis Latimer (1848-1928): Renaissance Man. https://invention.si.edu/invention-stories/innovative-lives-lewis-latimer-1848-1928-renaissance-man

- Henry Street Settlement. Our History. Henry Street Settlement. Retrieved from https://www.henrystreet.org/about/our-history/

- Latimer, L. H. (1880). Lewis Latimer Patent Drawing [Drawing]. National Museum of American History. https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/object/nmah_1313353

- Latimer, L. H. (1882). Process of Manufacturing Carbons (United States Patent Office Patent 252,386). https://patents.google.com/patent/US252386A/en?oq=US252386

- Lewis Howard Latimer. (2025). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Lewis_Howard_Latimer&oldid=1275020105

- Lewis Latimer House. Lewis Howard Latimer Biography. Lewis Latimer House. Retrieved from https://www.lewislatimerhouse.org/about

- Lincicome, B. (2024, July 1). Bringing Light for All. United States Patent and Trademark Office. https://www.uspto.gov/learning-and-resources/journeys-innovation/historical-stories/bringing-light-all

- Nichols, J. V., & Latimer, L. H. (1881). Electric Lamp (United States Patent Office Patent 247,097A). https://patents.google.com/patent/US247097A/en

- Roberts, S. (2024, June 13). Long in the Shadows, the Latimer House Museum Gets a Glow-Up. The New York Times, 12. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/13/arts/design/lewis-latimer-house-museum-queens.html

- Schneider, J. M., Singer, B. S., Davis, A. J., & Manning, K. R. (1995). Blueprint for Change: The Life and Times of Lewis H. Latimer. Queens Borough Public Library. http://digitalarchives.queenslibrary.org/browse/blueprint-change-life-and-times-lewis-h-latimer

- Spellen, S. (2014a, July 16). Queenswalk: The Lewis H. Latimer Story, Part Two - Electricity. Brownstoner. https://www.brownstoner.com/history/queenswalk-the-lewis-h-latimer-story-part-two-electricity/

- Spellen, S. (2014b, July 23). Queenswalk: The Lewis H. Latimer Story, Conclusion – the Edison Years and Beyond. Brownstoner. https://www.brownstoner.com/history/queenswalk-the-lewis-h-latimer-story-conclusion-the-edison-years-and-beyond/

- Thomas Edison National Historical Park. A Few Gifted Men Who Worked for Edison. U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/edis/learn/kidsyouth/the-gifted-men-who-worked-for-edison.htm

Cover Photo: Photograph of Lewis Latimer via Wikipedia; Arc Lamp Components via Smithsonian National Museum of American History; Edison Incandescent Lamp Drawings via Wikipedia; Drawings from "Process of Manufacturing Carbons" patent via Google Patents; Drawings from "Electric Lamp" patent via Google Patents.